‘Ānō me he whare pūngāwerewere’: Launching Whaea Blue by Talia Marshall

9th Aug 2024

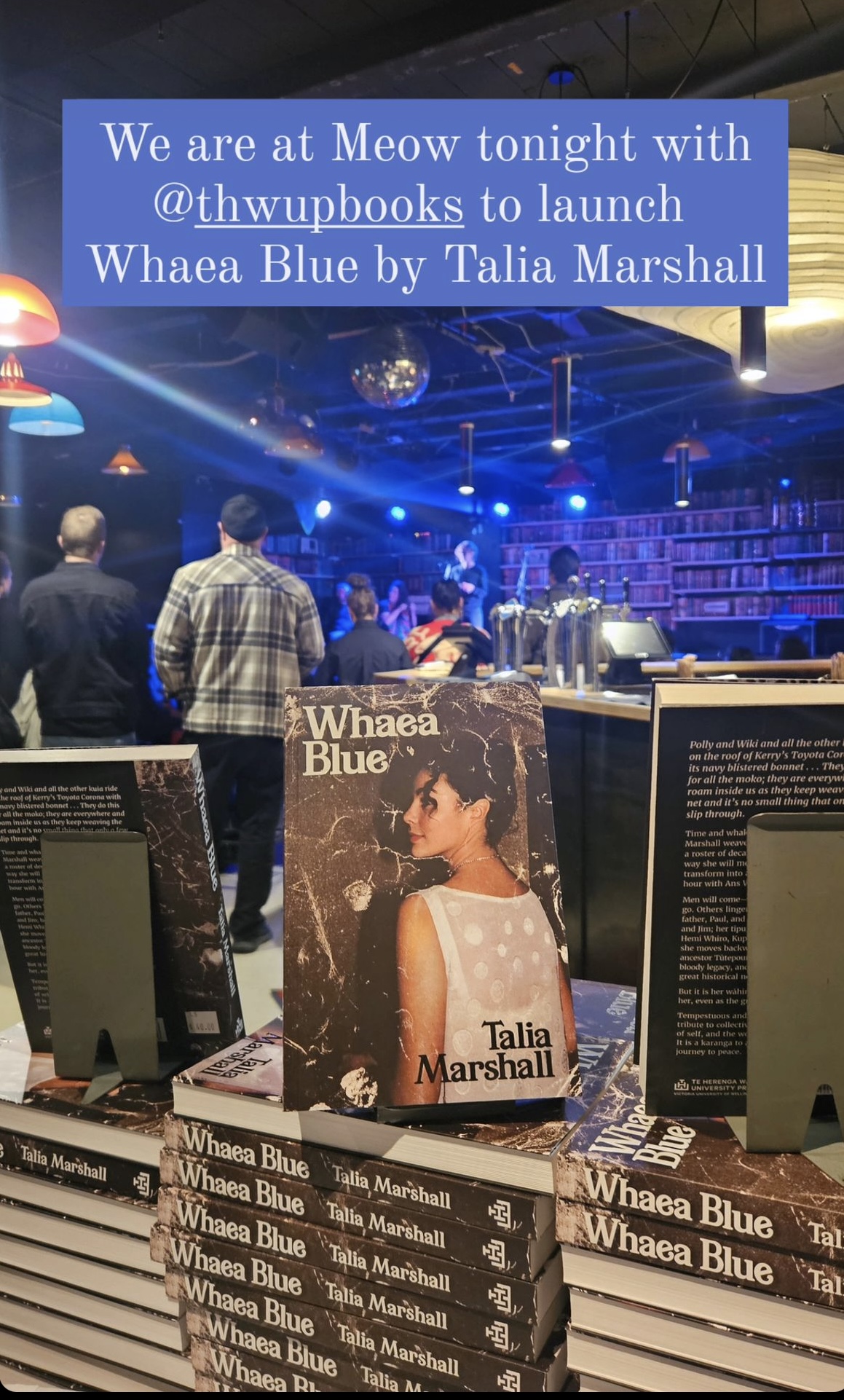

Kua tae mai te wā! On Thursday 8 August at Meow in Wellington we were thrilled to launch, at last, Whaea Blue, Talia Marshall's stunning memoir. Thank you so much to everyone who came to support and celebrate Talia's work. Special thanks to Meow for hosting us, Unity Books Wellington for selling books for us, and Tohu Wines for their generous contribution. Thanks also to Emma Hislop, Jonny West, and Talia's editor, Jasmine Sargent, for their beautiful kōrero. And especially, especially, thanks to Talia for this book.

Below, you can read Jasmine's speech, followed by Emma's, followed by Jonny's. All are must-reads.

In case you missed it, here's an excerpt from Talia's book on Newsroom, where you can also read a fantastic two-part interview with Talia and Noelle McCarthy: part 1 and part 2.

Photo: @unitybookswgtn Instagram

Jasmine Sargent

Whaea Blue has been many things under many names. It was called Boy Crazy, then Man-eater, then Tutū, Fire in the Greenstone Room, The Queen of Kō, War of the Rātā, The Year of the Taniwha, Tutū again, and then finally, Whaea Blue. It has been called memoir, a self-help manual, auto fiction, actual fiction and a book of essays. Its shape has morphed and moved. The whole thing has been written and written over in a million tiny ways, parts of it have flowed in and flowed out again without gaining purchase. Other parts have been cut, woven and tied off before unravelling and reforming in an entirely new shape.

Things happened. People died, ghosts came back, boundaries shifted, memory turned.

How do you tame something so alive? You honestly can’t. It was a genuine surprise to me when it arrived in my hand, contained in this shape with edges and covers, pages, a standard format—all things that suggest that the content is fixed or exhaustive, when in reality, it is expansive and forever expanding. Whaea Blue has existed for years, decades and centuries before now, carried along whakapapa lines to emerge with Talia. Each page carries with it another fifty of context, of the unsaid; each chapter has had multiple other lives or iterations, some of which I’ve read, some of which have never existed on paper.

You feel it all when you read this book. The world-building is powerful and the undercurrents are strong. The hidden narratives, the unnamed shadows, the silent experiences are all jostling at the edges, just outside of the picture. And Talia has the phenomenal ability to pull in the threads and form a path for the reader, where the unspoken sits as a presence rather than an absence.

I first read an early version of Talia’s manuscript when I was on parental leave in 2022. I had returned to Gisborne to reconnect with my whānau, my whakapapa, and learn my mita, and so that our son could be born closer to his whenua. As I pushed through my seventh week of sleep deprivation, new-parent delirium and the wavering borders of Who-Am-I-Now, I realised my reconnection journey was not going well. I hadn’t left the house. Then Talia’s manuscript arrived.

And I would argue that this was the perfect time to read it. Talia’s incredible, deft, intelligent, extraordinary writing met me among all of my scattered parts and inspired me to reassemble myself as all of the things I still was and could be: a reader, writer, editor, mother, sister, friend, daughter, partner and uri of my tīpuna.

It was the perfect time to read it because I was at my most fluid and malleable, and I think this is the ideal space for anyone to experience Talia’s work. It made an intricate and compelling sense to me—in the way that, in the depths of an altered state, the altered state itself makes sense—in the way that a dream makes sense when you’re in it, or you can discover an answer that feels ubiquitous that, on waking, on sobering, you can’t quite find the shape of. And then it’s a dragon—or maybe a taniwha—that you’re forever chasing.

I guess what I’m saying is the best way to experience Talia’s writing is to allow the freefall, to relinquish control. To calmly let yourself be carried away in the rip, trusting that, in time, you’ll return to where you’re meant to.

Because Whaea Blue never stops moving, and there’s no telling which direction it will pull you next. On a book level, we move in time from the past to the future, to the immediate, to te ao tāwhito, to an imagined past or future, and sometimes we’re in all of these times at once. We are in Wellington, in Dunedin, in Gisborne, Te Araroa, Pōrangahau, Nelson, Auckland, the deadly village by the sea, Foxton Beach, Aramoana, the Sounds. Sometimes we travel by bus, sometimes it’s a ferry, sometimes we’re in an old Audi—and sometimes that’s where we’re living. Our elderly Jack Russell, Tonka, is always there, and he’s usually pissing on something.

On a paragraph level, you’re tumbled through mercurial observations and narrative shifts so fluid and convincing that it’s not even a matter of ‘relinquishing’ control: you’re miles out to sea without even realising that you’ve stepped off the shore.

And on a sentence level you are—and this is a sentiment I hear often—sitting among the best, the most stunning, writing produced by a writer from this motu. There’s no one better.

So how do you edit a book like Whaea Blue?

You edit the entire thing, only to find that it has been rewritten in tandem. You start over. You respect shifts in tense, because sometimes it’s more Māori—more Talia—that way. You learn to send short emails with only a couple of questions, or one question, or half a question. No questions—you pick up the phone. You push the publication date back, and then you push it back again, and again, and again, because you’re working on Māori time. You send your cousin around to Talia’s house to pick up page proofs because you can’t be certain that they’ll make it to you otherwise. You beg and beg for the photos that you know are in an album somewhere in her house, then doctor the resolution of Facebook screenshots instead. You navigate through broken phones and three broken laptops. You receive fresh chapters in the week before it goes to print. You spend a full work week on one continuous Zoom call, trying to iron out final details. When Talia stops replying to emails, you rely on Twitter for updates:

Torturing my editor doing line edits in Google Docs on my phone and sending eight versions LOL

I am on my last line edit of like 38 chapters. Pray for my editor pray for the reader pray for my dolphin taniwha screensaver pray for us all.

Voiceover: Talia has been telling her editor that she does not have access to a scanner for months, this morning she realised there is an old printer in her study, a place she almost never enters.

Space invaders: a love story

Editor: how is it going?

Me: Great I’m up to 35

Editor: chapter 35?

Me: Level 35

To be fair, sometimes the updates do come to you directly, like this email:

Kia ora! Sorry I missed our

zoom, I got arrested.

Do you have a cell number? Can

you email when I can call you? Hope yr well!

But apart from all of that, you start to become as well, if not better, acquainted with someone else’s whakapapa as you are with your own. You get to watch the cogs of artistic genius turning, generations of storytellers culminating in a single incendiary, extraordinary voice. You get to talk through some of the underside of the iceberg. To build a friendship. And it’s a privilege, a career high, and definitely a taniwha that you’ll chase forever.

There’s a whakataukī that seeks to praise brilliant artistry. ‘Ānō me he whare pūngāwerewere’— ‘As though it were a spider’s web’. In every sense, this is Whaea Blue. It is art in its most breathtaking form; it is woven from a million threads; it is delicate, vulnerable, unique; it’s something to ensnare us, and we go willingly.

But that’s also Talia.

Tēnā tātou katoa.

Talia with Merran Tandy, Nelson, 1997. Photo: Masoumeh Mokhtar

Emma Hislop

Writers like Talia Marshall don’t come along very often. I knew about Talia’s writing before I tried to befriend her online, sending her annoying messenger messages. The way she wrote with precision about complicated, flawed relationships was something I aspired to do in my fiction. Immaculate sentences. More importantly, I knew she was from Dunedin, where I whakapapa to, and I was desperate to make connections. Talia wasn’t just Māori, but a Māori writer from Ōtepoti whose work I loved. After a few messages, she sent me a voice message. She was suspicious, she said, like many of us, she had been burned before. Perhaps we could talk on the phone. Yeah, I said. I got it.

We discovered her favourite place in the world is very close to Pūrākaunui, the place my tīpuna are buried. When Talia asked me to say a few words tonight she reminded me of this connection we share and this is one of the things I love about Talia, connection is everything. Also she’s convincing. Mostly, she’s guided by whakapapa and this sense of place. Her worldview feels 100 percent Māori, something my own colonised thinking often seems to want to distort. I said I hated public speaking but I’d come for the kai. ‘And only if I can give you a hug,’ I said. Talia is not a hugger, writing ‘If I know a hug is coming, I will think, sometimes for days in advance, about how the hug can be avoided.’ I can attest to the truth of this, at a recent hui at Orongomai I watched with amusement as Talia turned to stone each time kaituhi went in for a hug goodbye. It had felt like a win to get Talia out of Dunedin.

My second request – I want to meet your mum. Talia’s mum holds ICON status in the book.

Near the beginning of Whaea Blue, Talia writes, ‘I suppose one of my many problems is that I think I can remember everything when really there are all these little holes. And I fill them in with the silly putty of my imagination.’

Whaea Blue places extraordinary faith in the power of subjective memory. Talia started writing by writing poetry and has spoken in interviews about the book being a monstrous hybrid, a chance to dabble in genres and figure out the kind of writer she is. Like Talia, Whaea Blue defies classification, and, like Talia, it’s astute, wild and smart, sometimes hilarious. And she knows exactly what kind of writer she is.

In a recent interview, Whaea Blue was described as a debut novel. I messaged Talia, full of consternation on her behalf. ‘Maybe it is a novel,’ came the reply, again blurring the question of how much or how little of this story is filled in or invented. I asked Talia about her memory. ‘Some of its embellishment,’ she said. ‘But I’ve always had that ability to notice and record, it’s like I’ve got a giant Filofax in my brain, just downloading constantly.’

What Whaea Blue is or isn’t is just part of the story. The unapologetic voice is Talia’s, but it's a container for other people’s stories as well as her own. If it’s tough in parts that is unsurprising given the roughness of the road. Unlike me, she has no reservations about the accuracy of her own memory – describing events she has observed or closely experienced herself with precision – but about the determination to always create a good story. It’s SUCH a good story.

Maybe the most important memories are those you make up. The sense of being outside time, being responsible for another life, these are familiar feelings, and yet Whaea Blue reminds us how amplified they are when you add in the writer’s feeling of being a young wahine raising her son on her own. But this is only another story she’s grown up with.

The tāne she writes about – Jim, her lovely grandfather; Paul, who she first meets in her teens, and won’t call Dad; Mugwi, Paul’s Dad; Roman, the father of her son; plus a number of exes are embedded in these stories. She writes, ‘Jim is the reason I feel so at home in the water and believe in the power of words.’ It's her trip with Dieter that takes her into pure o, because her attachment to him becomes the site of her vulnerability, and that pulls her out again. Her love for Roman is precious and more solid – she realised that the ‘fresh insane love’ she feels for her baby is her Mum’s old feeling for her, completely different from the kind of in‑love feeling she expected with a man. It’s Isaac she’s seduced by, with a meth addiction and on the run. Someone who also reads the paper over breakfast in the morning. She writes, ‘I miss the way he would say I love you at the dinner table while I fed him the cockles we’d collected from the inlet, cooked with wine and cream and mopped up with rewena bread from the supermarket.’ Like whakapapa, things in Whaea Blue are complex and have many layers.

When love fails, she gives up on hetero relationships. Part of what makes Whaea Blue so moving is that we can feel this shift as she writes, writing herself into the realisation that she has to leave the insanity of Ben in order to protect herself and her son.

I asked Talia if she had a favourite chapter and she said there were quite a few she didn’t like, but probably the last one – and Jasmine, her editor and now friend, loved that one so much she wouldn’t let Talia put a photo in it, as she couldn’t bear to interrupt the text.

Tomorrow morning I fly to Ōtepoti for another kaupapa. It will be my son and his cousin's first visit to Puketeraki, our marae. I tell Talia we will also visit Pūrākaunui. ‘Yay. Get cockles,’ she says. ‘And leave them for a day before you eat them, to let the grit settle.’ I imagine me and the kids going for cockles at the inlet. Talia somehow fills in the holes in my story, too. We talk a lot about writing. She has a story for everything. And she cracks me up. The other day she suggested I be kinder to myself. She said, ‘And then you’ll be kinder to your characters.’ To think I paid a therapist for years. It’s this understanding of people which is part of her strength and her gift as a writer. I imagine all the stories Talia has in her head.

In ‘Karanga Mai’, the last story, Talia takes us into the afterlife:

‘And here is my karanga back to the kuia. It is reedy and it wavers but eventually I will be let onto the silk that runs through the cobweb glinting in the light between us and us. I permit – no, I enjoy – their shoves and the impossible task of admitting to myself that I am just a mongrel with desperate eyes and not a lost princess.’

Everyone please buy this book.

Jonny West

He mihi nui kia koutou i tēnei pō.

He mihi nui ki ngā tangata whenua ki tenei whenua, ki tenei moana hoki, Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Ko wai a Tara? He tupuna a Talia.

He mihi nunui kia koe, a Talia, te wahine toa, te putiputi o te pō tēnei.

He mihi nunui kia tātau katoa.

Ko wai ahau? He Pākehā ahau no Ōtepoti, ki Te Wai Pounamu.

Ko Alan rāua ko Deb ōku matua.

Ko Kate tōku wahine toa.

Ko Kage, Hana, Rosie, Grace rātou ko Henry aku Tamariki.

Ko Jonathan – Jonny – tōku ingoa.

Tēnā koutou tātau katoa.

My name is Jonathan – Jonny – West. I met Talia when she was sixteen. Never sweet. I was eighteen, less sweet still, but sweet enough on her, of course. You’ve seen the photos. I only confessed this to Talia, once, years later, in the student pub the Loaded Goblin in the bowels of the university. She was very good about it, just looked at me and sighed, Oh Jonny. Meaning, for goodness sake, put it away. And so we drank some more and went back to our gossip. Anyway, this is as much to say, that I guess that’s why she might have asked me to speak tonight – actually, to stand in for Steve Braunias, who’s abandoned her at the altar, as it were – that we’re now friends of thirty years. So: everyone – a first toast to Talia, and the gift of her friendship!

I mention this because Becky, on the back of Whaea Blue, says this is a book for the wāhine – which of course it is; it's not a monstrous hybrid as Talia says, only its mother would ever call it that – but it is a weaving of many things, and one of the loveliest threads is a love letter to some of her besties. I’m not one of those – they are her wāhine – but Talia has a wider gift for friendship even she may not quite realise. Talia told me to tell you she was once a holy terror, but I remind her we haven’t really had a fight in thirty years. Not one I can remember, anyway, though I’m a goldfish and she’s an elephant, and maybe that’s why we get along.

That, and the fact I’ve been in Wellington the past fifteen years, and we haven’t seen so much of each other. Whaea Blue recounts the years I knew Talia best, and I love her for remembering our people – and I’m thinking most of Nicky Glynn, whose bed she was sharing for a while when I flatted with him, for Nicky, brilliant Nicky, died young, and when Talia’s written about him here and elsewhere she brings back for me his ever so quick cleverness, and deals with his darkness with tenderness and delicacy.

The stories she tells of the years I haven’t seen her so much, they’re often hard to swallow. The writing – the sly, wry, all-seeing eye of it, sentences sharp enough to slit wrists – the eviscerating self-awareness, the long looks at the pain of our pasts, distant or all too otherwise. She’s so hard on herself it’s hard to read. Like she’s decided she’s a dish best served filleted, and raw. Talia sashimi.

If not a monster, nor a memoir, what is Whaea Blue? Maybe its a meditation. Talia, so restless, always moving if not fleeing – houses, cities, men – grounds herself in the language she finds here. If someone’s drawn to read the dictionary or the phone book (does anyone else miss the phone book?), for someone, such as that, for such as Talia, words are home. A peace making.

But, publishing? Releasing a book into the world? A peace offering?

Talia’s not shy; she’s quite unreliable about that. She’s not shy of a fight either. She’s horribly alive to the risks she’s taking. Man on a Wire, only a woman dancing on a line of words for all to see. All the worry and the warnings she recounts about picking at what’s forbidden. That’s the truth-teller's burden; the seer’s curse. Luckily, one of Whaea Blue’s lessons – heed it! – is don’t fight Talia. Another, though – don’t fight it, Talia. The words need to come out! And it will all come out, in the wash.

Because one thing Whaea Blue most certainly isn’t, is an orphan, no. It will have readers, owners, many parents. A book so alive it’ll raise readers from the dead. So: raise your glasses once again: to Whaea Blue, and to Talia.

He

putiputi koe i kahotia

hei piri ki te uma, e te tau.

He tau aroha koe, koronga roa

koronga i ngā rā!

Maku

ano rā koe e atawhai

kei kino i te ao.

Kia piri tonu mai

hei putiputi pai

i kato-hi-a!

You

are like a flower plucked

to be kept close to my breast, oh darling.

You are the beloved one I have long desired

desired through all my days!

My care will be for you

to keep you from being spoilt by the world.

May you stick close to me always

a lovely flower

that has been plucked!

Whaea Blue (RRP $40, paperback) is available now from Unity Books Wellington, all other good book shops, and here on our website.