'The dark side of Country Calendar': Launching Peninsula by Sharron Came

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 3rd Oct 2022

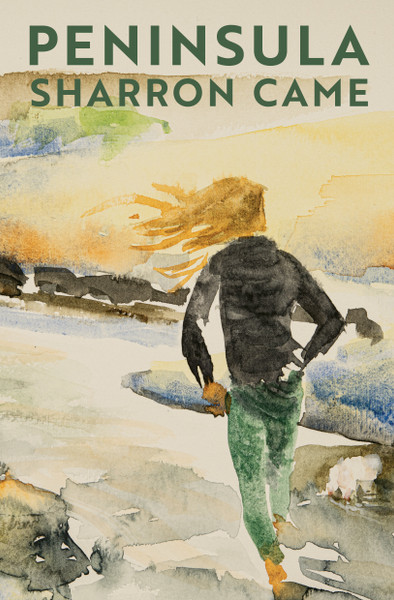

Last month we launched Sharron Came's debut book Peninsula, a book that might be called a story cycle, a set of interwoven stories, or even a novel in stories. Really it's an indescribable book, but novelist Damien Wilkins – who was Sharron's supervisor during her MA year at the International Institute of Modern Letters – did a pretty great job of describing this wonderful book in his launch speech.

I’m so happy to say some words about this very special book and I kind of grin whenever I think of it and think of Sharron. I was lucky enough to be Sharron’s supervisor when she did her MA and when she wrote most of this collection of stories. To be honest, I didn’t do much and I’m also aware that I stand in a line of teachers and readers who Sharron acknowledges at the back of the book. So there’s been a solid community around the book and Sharron was very open and curious about what readers had to say about her work, keen to absorb what seemed useful, but she also tended to be ahead of you, to have a plan, to carry a great deal of necessary self-possession. She’s a real writer — and she’s also a trail runner so she knows about endurance, the long hard damp slog of the page. And she just got on with it, building this amazing interconnected world, this wide and deep portrait of a rural community, which is Peninsula.

You might have seen the interview Sharron did in the DomPost recently in which she reminded us that not all writers begin when they’re young and she mentioned my old friend Barbara Anderson as one of her heroes in this regard. As many of you will know, Barbara did Bill Manhire’s writing course in her fifties and didn’t publish her first book of stories until she was almost 60. Now you might think the later start will result in a writer who is heavily Wise and full of Important Things to Say in the slow measured voice of reckoning and reason, and thank god, the opposite is the case. Sharron is a very different writer to Barbara but her work carries that same swiftness, that same feeling of leaps and bounds; that sense of things stored up, suddenly released. Yes, there’s that feel for the span of lives, for the breadth of experience—but communicated at pace, buoyed up by mischief, and with the mystery still intact.

There’s something else too—this really startling quality in Sharron’s writing—the sense in which it dwells in two places simultaneously—I mean she writes powerfully about what people are doing now, and how their voices sound, how their minds work and how their actions unfold in the immediate moment—while also suggesting the great canvas of time which is this moment’s backdrop and which sits hidden, like a painting concealed behind the painting we’re looking at.

It’s one of the great powers of fiction, I think, to help us feel this doubleness or even tripleness of things— ‘what we are’ meeting and intertwined with ‘what we were’ and somehow suggesting ‘what we might be’. That’s getting pretty metaphysical, sorry, but these completely earthbound stories hold a lot of reflective energy in them.

I think this book casts a really unusual spell. At first blush it all seems as New Zealandy as sheep dogs, septic tanks and muting the TV but keeping it on when visitors arrive. As one of the characters suggests, you’ve got to face ‘the beer guts and the chauvinism’; there are drugs and deaths and secrets, and the hairdresser in town who plucks the unwanted hair from the ‘bashful wives of farmers.’ Sort of like the dark side of Country Calendar. Then you notice that all your assumptions about types of people are being challenged. Characters get to be themselves rather than examples of something. You feel the creeping poetry of lives coping with change and how this vividly imagined world of tramping huts, bush runs, and squash clubs contains other worlds. Suddenly we’re in a place of dreaming—the book opens with a farmer closing his eyes in a warm barn and starting to see the world behind this one; a place where the wind is ‘smearing clouds like butter across toast,’ where a man feels the touch of a woman’s hand on his arm and converts it to a taste, ‘bittersweet, almost soapy like a ripe feijoa.’ The language matches the characters, emerges from them, but also lifts them; when Di, the mother, is in hospital, she feels ‘like a scrubbed potato, all raw’; or there’s Shayne, with his voice ‘like a chisel rasping on wood’; Greg has ‘squash ball sized calves’; Rachel, the daughter in the title story ‘Peninsula’, thinks of returning home as instinctual, ‘like opening a hot oven with your glasses on and being surprised when they steamed up. You feel silly when it happens but the insight doesn’t stop you doing it again’ . . . and this kind of descriptive relish extends to the natural world too, where a sky is ‘the colour of sunburn and hurts us’ and how about this one from a brilliant and scary story called ‘Tramp’ - ‘The bush acts like a shower nozzle controlling the rain pressure.’ And of course it does, and of course sunburn is a sky colour and a touch can register as a taste—it’s just that we’ve never read this before. And why do we always open the oven door with our glasses on and call out, I can’t see! I can’t see! The same reason, this book tells us, we decide to go home and visit our brother, thinking it will be different this time . . .

As the characters get ambushed by the past, this intricate pattern emerges of avoidance and confrontation and it stitches the book together. We feel the approaching loss of various things: ways of living, natural habitats, parents, friends. But also the possibility of new things in their place, hopeful changes. In an aching story called ‘Anniversary’ there’s a beautiful reunion between two blokes, as they remember their dead friend who was killed driving drunk when maybe they could have got his keys off him. This pair, formerly heavy drinkers, end up toasting the dead friend with two bottles of ginger beer—they’re sort of amazed at themselves for being reborn as sober men, capable of providing a guest with actual food. It’s very funny, which is another thing this book does. Anyway, then one of them thinks back on the time they drove to the beach to watch a sunset but they stuffed up the timing and had to pull the car over before the beach and they watched it there, with their friends. This is how the writing summons it: the sky gliding ‘from pink to tangerine. Fragments of light caught on the edges of Kiri’s and Shayne’s hair like a golden net.’ It’s lovely in itself—that image of the light in the hair—and it’s also incredibly poignant since that word ‘net’ gets us to think about how these characters are also in a kind of net, the net of their connections to one another and to this place. That elegant noticing also belongs to the central character Ritchie, who has returned to the district for this anniversary—just another moment where a character shakes free of our judgements. I hardly need to say that Sharron is great at writing men—she really makes our inarticulate selves sing!

The final story in the book is called— satisfyingly—‘Survivor’, about a high school camp which teeters on the edge of disaster. Sharron has a terrific feel for this edge. Her writing’s Emergency Locator Beacon is often signalling from perilous settings. But this tense story moves towards a new beginning, as the lost teenagers walk out on to the beach and approach the water—and they see the luminescence at low tide, and they’re drawn to it and they begin to stir it—one of them thinks it looks like nail polish, which is another off-hand moment of brilliance from Sharron, and the narrator thinks of jewels or silvery tadpoles—they reach into the luminescence and it gives them, the narrator tells us, a little charge of energy and they know then they don’t need to be rescued and that they can walk out by themselves, altered, shaken, ready.

So

finally, with that image of glittery power and communal resourcefulness, and

thinking of what these characters get up to – tramping, running, camping,

planning, getting lost, returning, remembering, escaping, dreaming . . . I want

to suggest that when you pack for your next adventure or just your next

trip home, take this object with you . . . this book is not that heavy, and

anyway, it will sustain you, energise you, and get you through the night . . . Now

can we give a huge welcome to the author – Sharron Came!