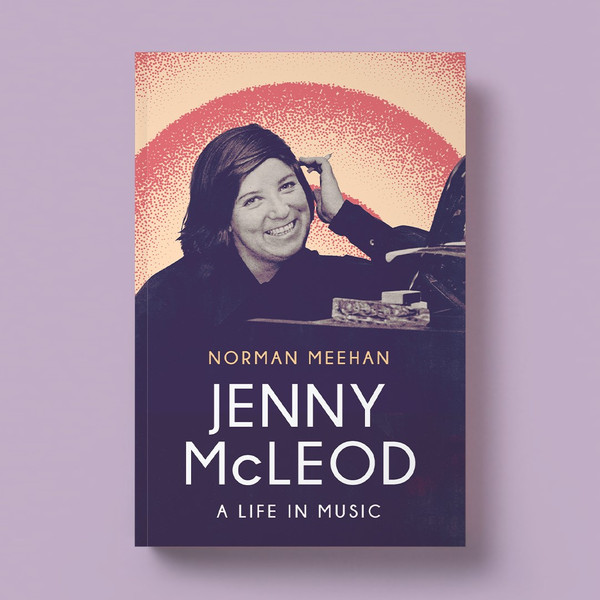

Jenny’s restless curiosity and irrepressible spirit: Launching Jenny McLeod: A Life in Music by Norman Meehan

13th Oct 2023

On Thursday 12 October we launched Jenny McLeod: A Life in Music by Norman Meehan with a special event held in the Hunter Council Chamber marked with performances of Jenny's music by STROMA Trio, Ken Ichinose, Anna van der Zee and Liam Furey and Margaret Medlyn and Bruce Greenfield.

Michael Norris was there to launch the book. His launch speech below.

When I learned of Jenny’s passing, I was deeply saddened, for one of our last great senior composers had left us. She was a character, a personality, and a source of immense intellectual stimulation ever since, as a high school student attending my first Nelson Composers Workshop, I attended a lecture she gave introducing her Tone Clock theory to us.As I thought back on these aspects of her inimitable self, I decided to reread our last emails to each other, when, in the weeks leading up to her death, we’d communicated about a possible new publication of her unpublished manuscript Chromatic Maps. In my final email to her, I had requested some citations for a list of post-tonal music theorists mentioned at one point in the text.

She replied with characteristic insouciance: ‘Here you go’, she wrote. ‘This is about the best I could do, having completely forgotten the assembly of sources, motley no doubt.’

I smiled upon re-reading this exchange, for it had inadvertently captured her personality to a tee. Here was Jenny, still caring about getting her complex and monumental compositional theory out into the world, yet at the same time not really being one for getting bogged down in the weeds of academic exactitude.

As I looked through another email, one in which she had resiled from that widely accepted music theoretical term ‘post-tonality’, I couldn’t help but hear her broad accent and impish chuckle as she chided me: ‘But what does it mean, Michael? – ‘post’ tonality. ‘post’ means ‘after’. But I don’t agree that ‘tonality’ itself was ever ‘over’’. I realised I missed her a lot.

And so it was with great delight and not a small degree of emotion that I heard of the imminent publication of Norman Meehan’s new book that set out to trace the shape of Jenny’s life, and I am very honoured to have been invited to launch it into the world.

I was particularly interested in whether the book would fill in those chapters of Jenny’s life that I had heard rumours of, but never really had a full synopsis of.

And so to Norman: you’ve nailed it! Your new book, Jenny McLeod: A Life in Music, has managed with eloquence, grace and aplomb to not only capture Jenny’s restless curiosity and irrepressible spirit, but at the same time to vicariously trace, through the lens of her many and varied compositional pursuits, a history of Aotearoa’s post-war cultural renaissance. In your clear, lucid prose, you tell us a story, a story of how in Aotearoa in the 1960s, increasing access to international travel and sound recordings from abroad led to an artistic awakening not only to the wider world but also to our own place in it. Jenny’s time in which she ruthlessly pursued enlightenment in all shapes and forms in Europe and America speaks strongly to this. But in particular, it tells a story of how Jenny’s engagement with Māori culture was to become an increasingly central part of her sense of place and belonging.

But we might go further. We might say that your biography also tells us a story about the broader global dilemmas of art in a world that was still reeling from the trauma of two world wars. When we pick up the threads of Jenny’s first serious compositional pursuits in the early 1960s, the global art world is undergoing a serious bout of self-questioning. Fuelled by the co-option in the first half of the twentieth century of bland nationalist art by Europe’s fascist regimes, many reacted by creating art that actively denied such co-option or emotional superficiality. In musical terms, this found its expression in music of deep alienation, neurosis, surreality, irony, intellectual aloofness, science fiction, or even, in the case of John Cage, the absolute tabula rasa of silence itself.

By the 1960s, as Jenny had entered her twenties and her most formative years, music was still trying to figure out how to regain a connection with the tattered remnants of tonality. At the same time it was trying to avoid the saccharine subjectivities and racist, nationalist undercurrents of late Romanticism that now left a sour taste in the global mouth. Throughout this period you can see other New Zealand composers lurching between direct imitation of European figureheads, as in Anthony Watson’s heavily Bartókian string quartets or the strong whiffs of Stravinsky found in Edwin Carr’s music, and on the other hand, their subsequent repudiation, such as when Lilburn veered away from serialism after having been bored rigid at one of Stockhausen’s lectures.

For Jenny, while her two large-scale theatre works Earth and Sky (1968) and Under the Sun (1971) grappled with this delicate aesthetic balancing act, devising a language that was primal and accessible yet at the same time sophisticatedly chromatic, it would nevertheless take her until the 1980s to arrive at a compositional approach — the Tone Clock — that would truly reconcile this dilemma.

Norman’s story tells us of how Jenny’s lifepath followed a constant search for meaning, of finding a way to encompass different modes of being and expression, from the intellect pursuit of the teleological narrative of constant progress in European modernism, through to her abandonment of the intellectual for the reinvigoration of the spirit, through to the unfettered joy of popular music, through to reconciliation of tonality and atonality in the form of the Tone Clock.

A true musical omnivore, Jenny never denied any music’s reason for being. For her, music was a true continuum, a terrain across which she wandered, mapping its edges, taking detailed field notes, sometimes stopping to rest, at other times promptly moving on to the next location.

I recall an exchange at one of the annual Composer Workshops in Nelson some years back, when, now as a tutor, I had suggested to one of the younger students there that they might push their aesthetic a little further or investigate more sophisticated harmonic worlds. Jenny turned and immediately reprimanded me — again always smilingly — saying ‘No Michael, I thought it was great the way it was. Don’t listen to him!’ This statement was, of course, followed by her rambunctious laugh.

These many and varied interests finally found an intellectual home in Peter Schat’s Tone Clock. She discovered that in the grand Venn diagram of twentieth-century harmonic systems, the Tone Clock was in many ways the mother set, being able to account not only for the music of her beloved Debussy, Messiaen, Stravinsky, Webern and Bartók, but that it even had something to say about jazz, one of the most truly radical and harmonically adventurous developments in the twentieth century. Indeed, New Zealand jazz composer Ryan Brake has just completed recording a new album of twelve Tone Clock jazz compositions with leading English pianist John Escreet, which we look forward to being published in 2024.

The style-agnosticism of the Tone Clock shines through her own set of 24 Tone Clock pieces for piano, which range from quartal flavours redolent of Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage in Tone Clock Piece No. 1, to hints of Debussy’s prelude Canope in Tone Clock Piece No. 6, to the kinds of Stravinskian triadic mixtures found in Petrushka and Rite of Spring in Tone Clock Piece No. 7.

But it is probably her beloved teacher, Olivier Messiaen, who provided the most irresistible connection for her, with his so-called modes of limited transposition. These scales, through their symmetrical construction, resist the essential asymmetry of time. They open a space where time halts its inexorable progress. In his masterwork ‘Quartet for the End of Time’, the modes create harmonic loops that coil back on themselves in an eternal mystery.

While Messiaen’s symmetries and impossibilities invite us to contemplate the profundities of God, for Jenny, the Tone Clock seems perhaps to have been less an act of divine evocation, and more a way of capturing the lapping of the sea on rocks at Pukerua Bay, or the avian ambience of the dawn chorus on Kapiti Island.

The increasing appeal of Jenny’s Tone Clock to composers around the world has in recent years become starkly evident. Many of my third-year composers, on learning about it, choose to employ it in their own compositions, and in the last year alone, I’ve fielded enquiries from composers in South Africa, Australia, Chile, the United Kingdom and the United States, all eager to learn more about it, all of whom have found in it a vocabulary and way of thinking that so strongly resonates with their own aesthetics. There are now a number of PhDs and academic articles written about it, and it is my sincere hope that once I finally finish editing Chromatic Maps and get it out into the world, it will have a real, tangible impact.

But perhaps it is the light that Norman’s biography shines on Jenny’s deep relationship with te ao Māori that is the most interesting aspect of the book. For it tells a story of the gradual emergence of Aotearoa’s biculturalism in the 1960s, and what must be one of the first artistic positions that Pakeha, as tauiwi and tangata tiriti, had an obligation to address historical injustices and be actively involved in upholding the mana of tangata whenua. While continuing to mine the rich resources of twentieth-century European art music, Jenny’s music turned ever more to te ao Māori, to its reo, to its poetry, its art and mythology, all the while drawing on the natural soundscapes of the moana, the whenua and manu. From this perspective, she surely stands as one of our artists most deeply committed to the concept of cultural partnership.

For many of Jenny’s Pakeha friends, however, it will be the chapters in the book that deal with her discovery of and integration with her adopted whānau in Ngai te Rangi at Ohakune that will be revelatory. They cover in detail her musical, cultural and spiritual pursuits that many of us didn’t really get to see. This book has succinctly and warmly filled in the blanks.

A Life in Music is truly infused with Jenny’s words and Jenny’s character. When reading it, I could almost hear her knowing winks, her quick-witted ripostes and her teasing reproaches. Her voice, sometimes larger than life, echoes through every page. Norman: You have not only sketched the shape of a life but, through a certain miracle of the written word, you have captured her very spirit.

I’d like to finish with a whakatauki, one that we use from time to time at the New Zealand School of Music Te Kōkī:

E koekoe te kōkō, e ketekete te kākā, e kūkū te kererū

in English, the tui chatters, the kaka gabbles, and the kereru coos — in other words that the world turns on its essential variety, its difference, and, most importantly, its colourful music.

And for a life like that which was lived by Jenny McLeod, a life that crossed many worlds, that explored many forms of music, and that touched many others, we are all the richer for having been part of it.

Jenny McLeod: A Life in Music ($50, paperback) is available now.