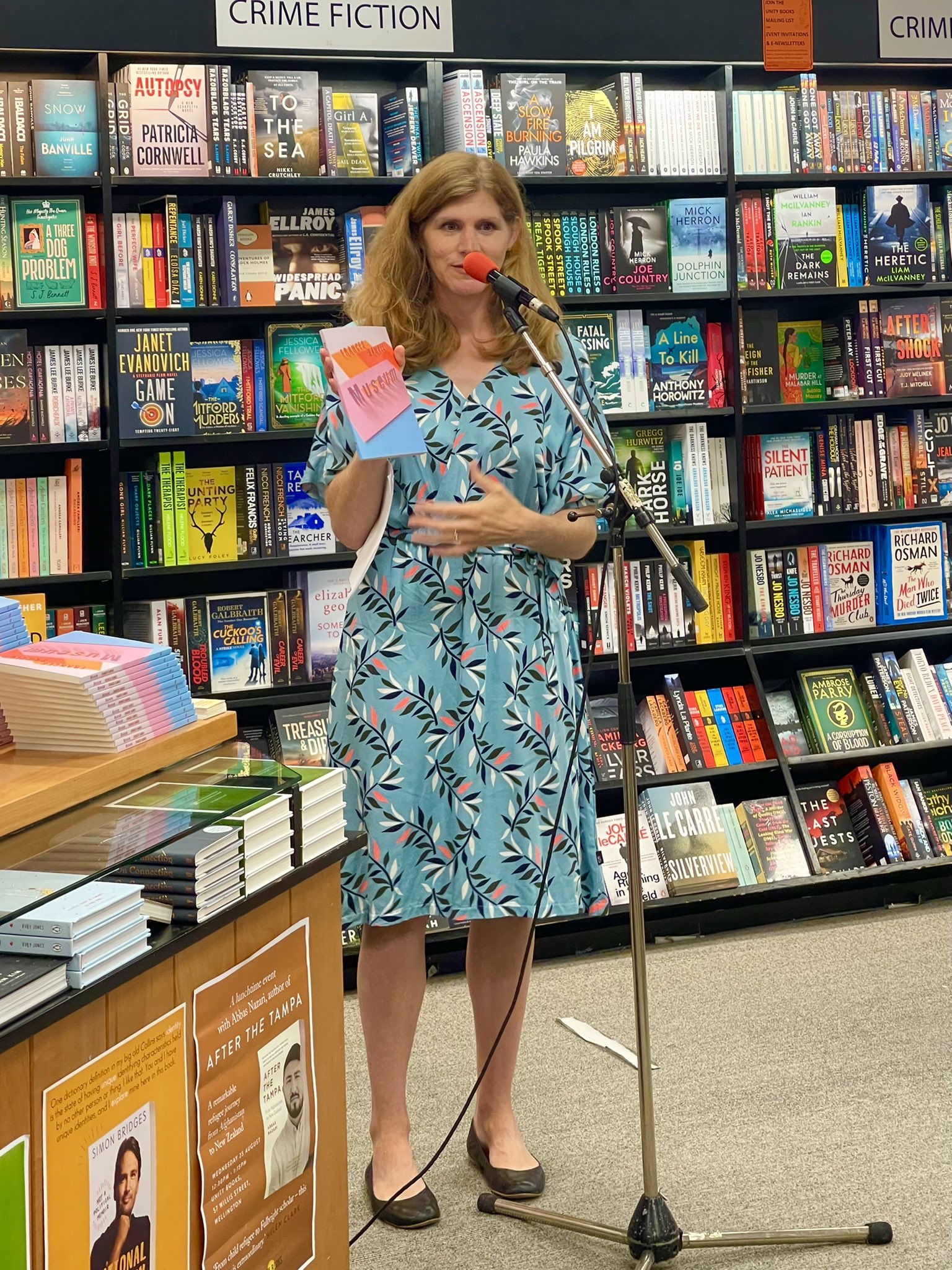

James Brown launches Museum by Frances Samuel

Posted by James Brown on 24th Feb 2022

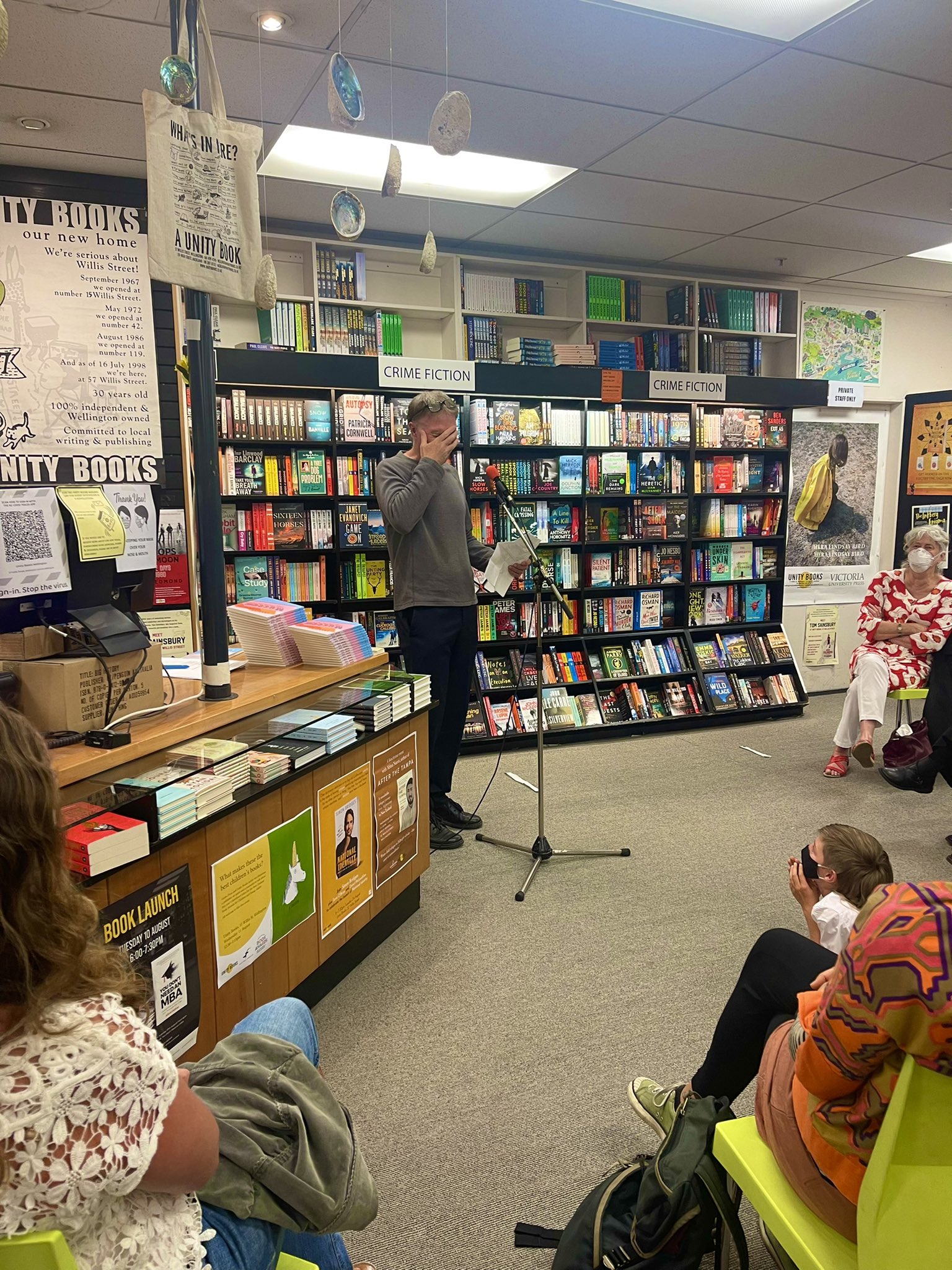

On Wednesday 23 Feb, against all odds, we celebrated a fantastic new poetry collection by Frances Samuel: Museum. Frankie was even able to persuade James Brown to give a speech. Here he is:

Kia ora tātou

A few weeks ago Frances and I were part of an email correspondence about an Island Bay writers panel. We both live in Island Bay – Frances actually lives just up the road from me. And a friend jokingly said to me, You should be on the panel, aren’t you the best poet in Island Bay? Well, when Frances’s manuscript turned up in my letterbox, I realised not only was I not the best poet in Island Bay, I wasn’t even the best poet in my street.

Frances worked for ages – over a decade – at Te Papa – in fact we sat next to each other, before the museum was divided into two museums and I went into Living Cultures (which was a sort of organic farm) and Frances went into the Future. (Maybe the reason the museum was divided was simply to stop Frances and me talking to each other.)

Frances’s Te Papa experience informs many of the poems in Museum. A lot are, as the blurb astutely points out, thought experiments. Certainly, when Frances moved into the Museum For the Future, I was no longer disturbed by the sound of her unfeasibly large brain whirring and clanking and churning out excellent label text. For a sample of this, I recommend the hilarious penultimate poem in the book – ‘Folding Tables’ – which is made up of lines from exhibition labels. Anyway … some of the poems in Museum are about museums as a concept, but most focus on weird and wonderful objects – what they might represent and how that might connect with the speaker. At times, the speaker themselves becomes like an exhibit – a worker trapped in a museum staring at an object framed in a case. And one way out is the story – in this instance, the poetry – that can be created around the object. So, in Museum, poetry is both an escape and refuge, as well as its own existential nightmare.

The Museum For the Future was concerned with the areas of Natural Environment and Art. Perhaps Frances writing labels about objects from the natural world and artworks encouraged the kind of daring jumps between reality and fantasy, and also in perspective, that occur throughout Museum. In one poem the perspective might be that of someone so big they can be seen from space, in the next, that of someone taking a walk inside the veins of their body.

Such moves make me wonder if Frances is perhaps a metaphysical poet. The metaphysicals, as we all know, were a 17th century school of poets who used physical things and elaborate conceits to reach for subjects beyond the physical world – ideas and emotions, say, and particularly god. But lumping Frances in with John Donne, Andrew Marvel and George Herbert seems a conceit too far, so perhaps we can label her a post-metaphysical. She has, after all, taken the movement to a new place, replacing god with art and science and thoroughly dismissing patriarchal posturing. Indulge me.

It should come as no surprise then, that such moves lead as much to uncertainty and anxiety as to insight and equilibrium. It seems to me that the overarching theme of Museum is in fact wellbeing. For example, sleep deprivation recurs, as it did in Frances’s first book Sleeping on Horseback. Museum, however, takes tiredness to a new level when, in one poem, the protagonist manages to fall asleep on their bicycle. And you don’t have to pull the unravelling thread of fatigue very hard to find … children – children who seem to have discovered the art of existing without sleep at all. They have much to teach us. So family life, and how it intersects with work life, is another of the book’s big concerns … and that naturally leads us back to wellbeing.

But for all

its gravity, Museum is not a heavy read. This is not the poetry of

exhaustion, it’s the poetry of replenishment. Museum is amazingly

affirming. It’s also simply an amazing book: it finds wonder everywhere,

particularly in language and its ability, in Frances’s shaky yet sure hands, to

transform and uplift. It’s clever, it’s questioning, but above all, it’s entertaining

and fun. Frances has a fantastic eye for the absurd. There’s a thesis to be

written about the absurd in this book. And on that random note, I thoroughly commend

Museum to you as a pleasurable panacea for our times.