Waiting for the right time to appear on stage: Launching Tracey Slaughter's new poetry collection

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 19th Aug 2024

On Friday 16 August in Kirikiriroa, as part of Hamilton Book Month, we launched The girls in the red house are singing, Tracey Slaughter's new poetry collection. This was such a great event, with readings by Tracey, Aimee-Jane Anderson O'Connor, Shivani Agrawal, Ethan Christensen and Liam Hinton, and out-of-towners Ashleigh Young from THWUP and New Zealand Poet Laureate Chris Tse. Thank you to everyone who came along! And thanks especially to Hamilton Book Month, Poppies Hamilton and the University of Waikato for your support and hospitality.

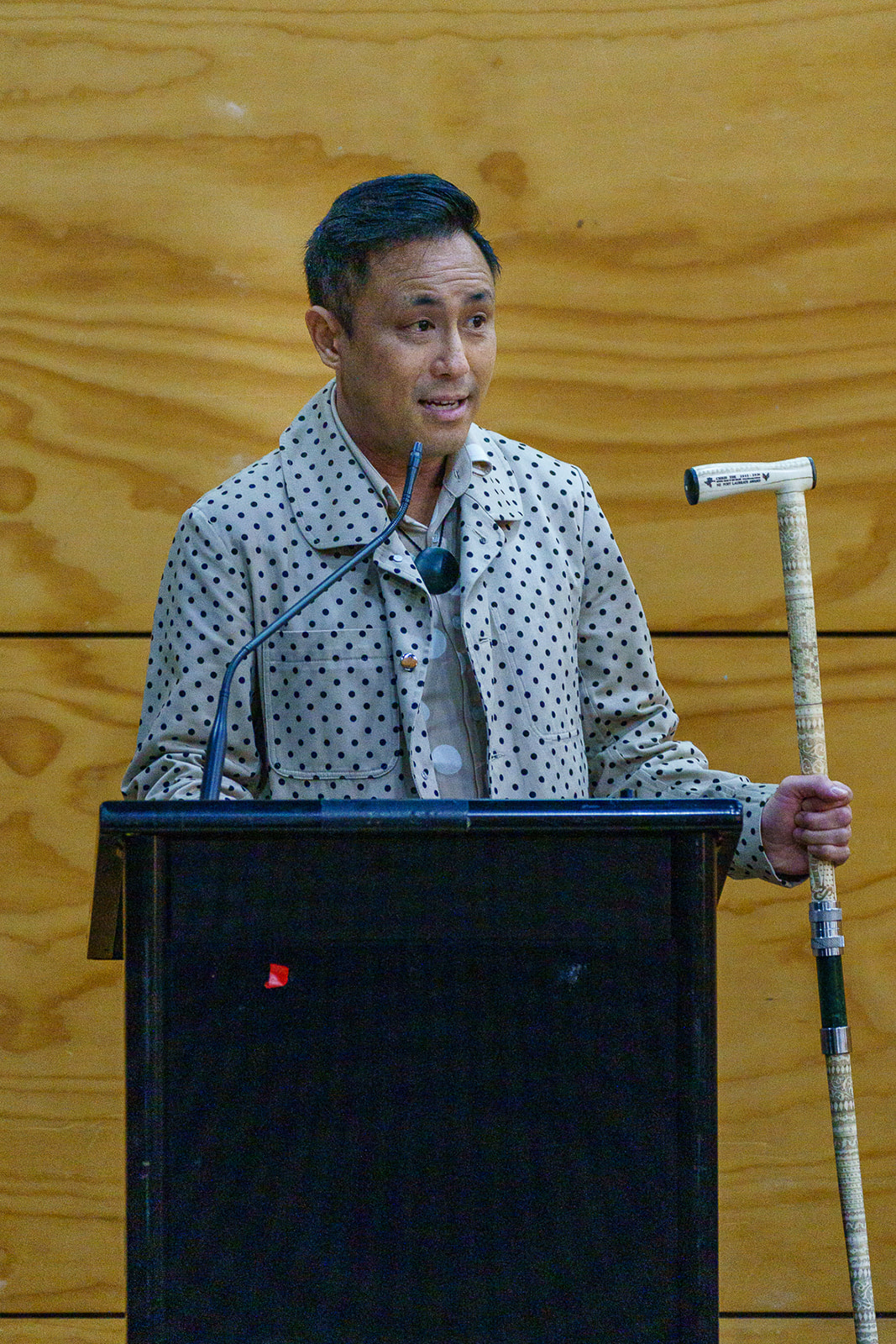

Chris Tse launched Tracey's new book; his words are below.

Tracey Slaughter reads. Photo: Ziad Thotathill

Chris Tse in action. Photo: Ziad Thotathill

I’m incredibly honoured to be launching Tracey Slaughter’s new poetry collection, The Girls in the Red House are Singing. I must admit that launching a book such as this is a daunting task, because the poetry contained between its covers is so stark and emotionally bruising, the repercussion of a poet reaching into the past to confront the trauma that they had hidden for so long as a means of self-preservation or to protect their loved ones. The Girls in the Red House are Singing is a deeply personal voyage into the heart of experience and expression, one that confronts difficult and often silenced topics: emotional and physical pain, sexual violence, suicide, and shame.

A few days after I finished reading Tracey’s book, a friend asked me what I thought, and I said that I felt like I’d been pummelled – the poems had left me shattered and breathless. I could still feel them like a lump in my throat, a physical manifestation of the shock of reading something so revealing. A part of me felt guilty for (a) wanting to soak up every scandalous detail and (b) being complicit in these revelations – I felt like the very worst kind of disaster tourist.

I also couldn’t wait to tell everyone I know

to read this book immediately because it is one of the most technically

dazzling and unique collections I have read in a long time. It is a truly

special book that can leave you in awe for both what the poet has chosen to

reveal and their craft – the ‘how’ of those revelations. Every word, sentence

and line feels so deliberate and charged with images that feel like they’ve

been borrowed from a parallel universe.

Take the book’s opening words – 'I crashed. It was choral. The glass formatted the light' – perhaps the most heavenly description of the moment of impact during a car crash. Those few words conjure up images of destruction and beauty, cacophony and music, and finality and revelation. One of my favourite aspects of the book is how it uses this blending of the hard and soft to pull you into its world – you are not just a reader, you become a trusted confidante and witness to everything that happens.

The aforementioned car crash is the starting point of the first section of the book, opioid sonatas, which recently won the 2023 Manchester Poetry Prize. The judges of that prize praised the sequence for its “forceful luminous brilliance” and said: 'We kept reading the poems aloud, revelling in the breathtaking momentum, beautiful language, and the galloping rhythmic quality. We felt that this was a genuine, unique voice – forceful and outstanding.'

opioid sonatas details the high-speed crash with disquieting lucidity, traversing the aftermath and circling the pain that a body must learn to constantly reprocess and live with, while also exploring the connection between other forms of trauma and chronic pain.

As the Manchester Poetry Prize judges said, the language in these poems has a breathtaking momentum. There are juxtapositions of words and images that feel slightly off-kilter but also strangely correct – echoes of the bewitching daze that comes with being in a car crash, that sick melding of flesh and metal, and how the world can look and feel changed after the fact. Some lines that I noted down while reading:

'She bleeds out / in an off-road church'

'Wearing the car like a flash in the marrow'

'the

bride in the right room is shaking like milk / & wearing her blood

backless

'the doctors are putting your blood on loop pedal'

These lines feature the body as a foundation to bridge the imagined and true realities of what it means to be in constant pain, and how the body manifests the after effects of a traumatic event, as a vessel for, and cause of, pain. In a poem from later in the book, Tracey reminds us that the body is cursed, or perhaps designed, to hold on to that which slowly destroys it:

Then I knew your body was the place where god had put his loneliness… I took off your shadow and lay it on a chair, where it stretched its wounds and watched everything.

Those lines are from a poem in the book’s

second section, psychopathology of a

small hotel, where the poet recounts attempts to reclaim the body by

searching for something that might release it from the pain it has felt in the

past. This leads them to seeking some form of desire to remind them of the

body’s capacity to hold both pain and joy – 'killing two birds with one taste'

– only to find themselves in a situation that might cause more harm than good.

Here, the speaker is a mistress, adulterer, and cheat, and instead of finding

release and freedom, their world is instead shrunk down and confined to the

dirty liminal space that is the cheap hotel room where an extramarital affair

takes place:

When I was young I thought churches were where the dead lived.

Now I know it's hotels.

This sense of dread and claustrophobia is a common feeling in the book, amplified by the spaces that many of the poems are set in, like the crashed car, the hospital cubicle, or the empty streets of lockdown. Some are forced upon the poet, others are sought out in an attempt to seek comfort: “We choose small places to breathe.”

At the same time, we are also told that “our task is to sing in this killer place”. We are also challenged to “sing a nice hymn if you know what’s good for you”. This notion of using the voice or the power of song to reclaim or reconfigure a space is propelled by the musical motifs deployed throughout the book. As someone who grew up singing in school choirs and will find any reason to gather friends for a karaoke session, I understand and thrive on the catharsis that singing can bring. Some therapists believe that singing is integral to treating trauma as it can activate the parts of our brains that process trauma and can decrease dissociation.

When I first saw the book’s title, I couldn’t help but think of the American singer-songwriter Tori Amos, who refers to her songs as her ‘song girls’. When introducing her songs in concert, she refers to them in the third person and reveals aspects of their personalities – they can be shy, boisterous, or silly – and she tells us that sometimes the song girls will wait for the right time to reappear on stage. Because of this association, I couldn’t help but view each of the poems in the book as one of Tracey’s own ‘poem girls’, which themselves are populated with the lives and voices of many other girls and women.

One the book’s standout poems, ‘teeth’, in the titular third section of the book, addresses a woman named Crystal who is beaten to death by her husband in front of her children. The poem explores the connections between women and their shared experiences, particularly when it comes to physical and sexual violence, and whether sisterhood as solidarity is enough when it comes to empathy. This event causes the echoes of the poet’s past traumas to rise to the surface once more.

The final section of the book, nudes, animals & ruins, contains what Tracey has called her ‘lockdown sonatas’. The poems in this section describe what it was like walking around her neighbourhood during lockdown and how this isolation and time alone revealed aspects of her personality and anxieties. Like the sections that have come before, it digs deep into the root causes of pain – 'the car accident refuses to stay / in the distance' and the memories of a past lover only heighten the loneliness and rage that swallows these poems, which perhaps brings us to the question that the book has been building towards: 'how do we find the strength to let go?'

It’s so easy to reach for words like ‘courageous’ and ‘brave’ to describe a poetic work like this that holds the reader so close to the flames of the poet’s pains. Perhaps it’s a symptom of being brought up in a country that doesn’t always value openness when it comes to talking about emotion or how the tremors of the past shape our present. Vulnerability is often deemed too hard to look at directly in the eyes.

There’s no denying that The Girls in the Red House are Singing is a tough book. One of the opioid sonata poems opens with the lines, 'You cannot be gentle with yourself. / You have to cut hard…'. And boy does this book cut hard, constantly showing us how pain and trauma can feel so relentless, no matter how hard you work to confront their sources or learn to live with them. Yes, this book is courageous and brave, but it is also necessary and momentous because it reminds us that poetry and writing in general are often as much about survival as they are about expressing ourselves.

Tracey: congratulations on the publication of

this stunning collection, and thank you for sharing these poems with us. I

truly believe that many people are going to learn a lot about themselves after

reading this, and that they too might find some form of peace from doing so. I

hope your girls continue to sing with uninhibited power and that their songs

are heard wide and far.

L–R: Liam Hinton, Shivani Agrawal, Tracey Slaughter, Chris Tse, Ashleigh Young, Ethan Christensen, Aimee-Jane Anderson O'Connor. Photo: Ziad Thotathill

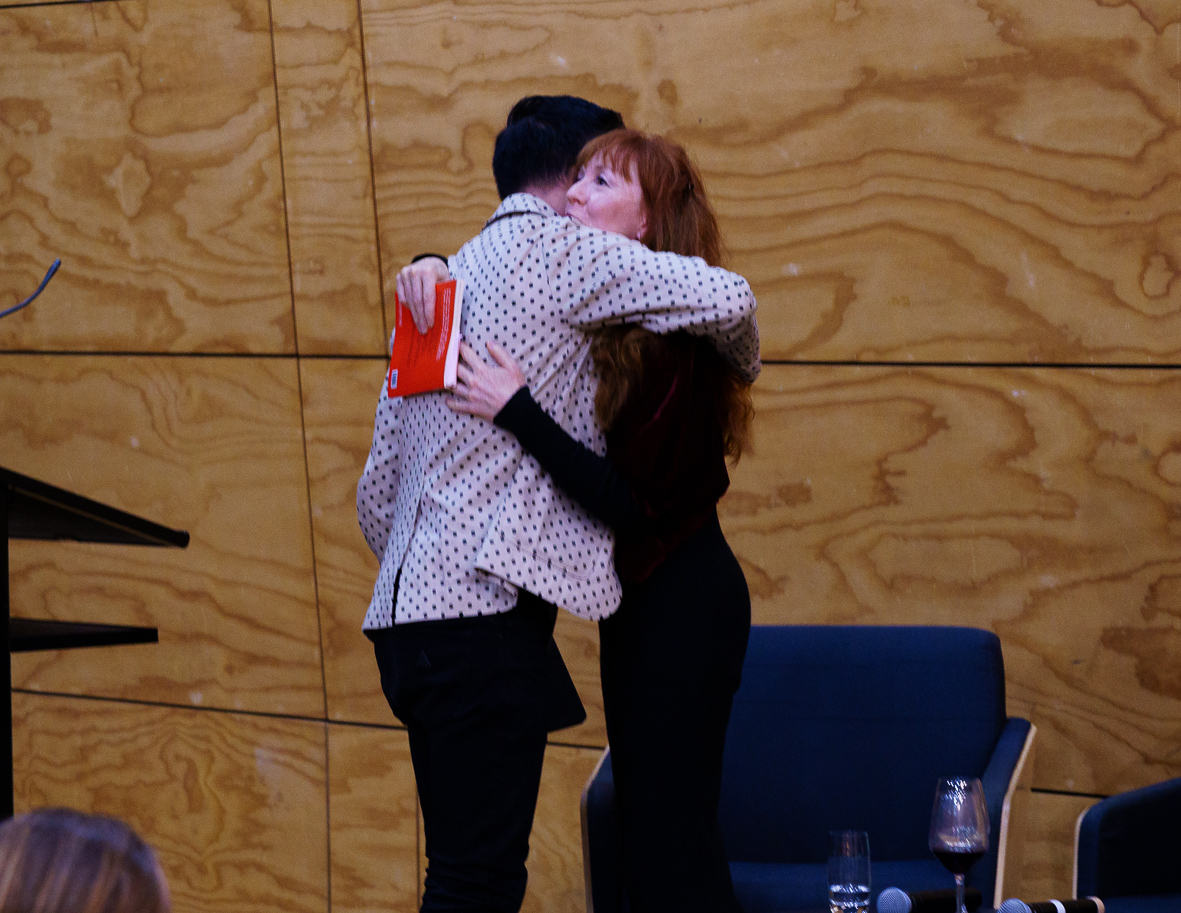

Chris Tse and Tracey Slaughter. Photo: Ziad Thotathill

Photo: Ziad Thotathill

Ethan Christensen, Chris Tse and Liam Hinton. Photo: Ziad Thotathill

The girls in the red house are singing (paperback, RRP$30) is available now from all good bookshops, and here on our website.