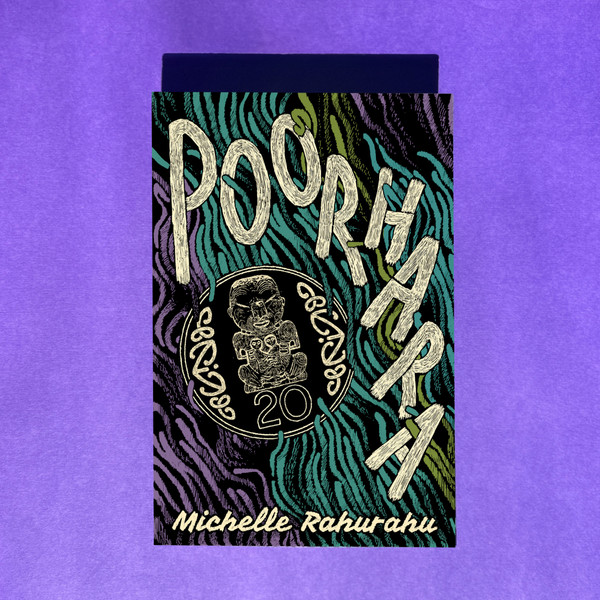

Rumblings are a sign of life, presence, communication and connection: Launching Poorhara by Michelle Rahurahu

Posted by Caoimhe McKeogh on 17th Oct 2024

On Wednesday 9 October at Unity Books Wellington we were very happy to launch the brilliant first novel by Michelle Rahurahu, Poorhara, with poems from essa may ranapiri and Ruby Solly, and a reading from Michelle. You can read the launch speech by Michelle's editor, Jasmine Sargent, below, followed by the poems from essa and Ruby.

Michelle with her pukapuka

It is said that when Ranginui and Papatuuaanuku were separated by their children, their grief was so intense that the tamariki turned their mother over to face Rarohenga, the underworld. At the time, Ruuaumoko, known to us as the atua of earthquakes and volcanoes, was still at her breast, and turned with her. In some koorero, his entrapment was an accident; in others he was intentionally left with Papatuuaanuku to keep her company. And so, the story of Ruuaumoko is a coin with two sides: on one, wrongful imprisonment; and on the other, loving companionship—all in the presence of grief.

If we take that coin and toss it, it lands on the cover of Poorhara. And if we open the book to the first page, we find Erin, a young wahine Maaori, sitting in her bedroom. She is watching a bulge in her ceiling, praying that it doesn’t burst. If the bulge bursts, the landlord might sell their house. If he does that, her whaanau will have nowhere to live. The scene slowly expands to reveal her two aunties and her uncle in the kitchen, and four or five young moko tearing through the hallways. The family has been in the house for twenty years. Today is their koro’s seventieth birthday, and Erin’s favourite cousin, Star, is on his way home to visit for the first time in years.

Before the end of the day, the bulge in Erin’s bedroom will burst. This is the first in a cascading series of eruptions, the first release of what simmers beneath the story, these characters, this whaanau, our people. Poorhara’s blurb begins, ‘It is 178 years since colonisation’, and the reverberations of that fact are everything. This is a whaanau who are strugglingto pool their dwindling resources, both financial and cultural, to ensure their continued survival in two separate and conflicting worlds. Like Ruuaumoko, Erin and Star are buried beneath stratified layers of grief, hurt, trauma and dislocation. And we see that same duality of experience—are the cousins held captive there, or are they merely being held?

*

I have spent many hours over many months with Michelle in this book. I have watched her gently guide Star and Erin through the rapids and the eddies of their lives, seen her send them in one direction, walk them back and coax them in another. I have knowledge of them that they’re yet to realise in themselves. I feel certain I could close my eyes and trace the shape of the narrative from memory, recalling every dip and peak.

So, when I returned to Poorhara recently as a reader, I was surprised by how much was still there for me to discover. It felt as though the ground had shifted, revealing layers and layers of meaning, and it was only then that I truly saw the expansive presence of Ruuaumoko. He is there when the bulge bursts. He boils beneath Star’s abcessed tooth, and in the mountain behind the urupaa where Erin’s mother lies. He sits deep within the family secrets and with their buried knowledge. He even vibrates through Star’s phone as Baycorp calls again and again. He’s there in every argument, every outburst, every opening and slamming of every door. His is a constant rumbling promise.

Ruuaumoko is also there when Erin erupts from a pile of blankets in the backseat of Star’s car, having secretly stowed away in the aftermath of their koro’s birthday. Star is rightfully shocked; Erin refuses to be taken home. Although, it must be said that this pivotal moment does not belong to Ruuaumoko alone—the discerning reader will sense the presence of another famous pootiki. This is Erin’s Maaui moment. And true to Maaui form, this will be the catalyst for all that follows. Desperate to escape, too scared to go back, spurred on by a restless need for connection, and on a quest for answers, Erin will convince Star to take a road trip to their ancestral whenua.

The difference between them and Maaui, Star will tell us, was that Maaui had a system of protectors, allies—he had people who would tear out their own jawbones, or pluck their own fingernails off, just to see him succeed. Maybe a cousin with a car was enough.

What Star fails to mention here is that this is not just any car—it’s a 1994 Daihatsu Mira with an expired warrant. It is one of the smallest vehicles known to humankind. It has one of those cassette-tape auxiliary adaptors. It is packed nearly to the roof with tissues, blankets, clothing, warm cans of Haagen, Big Mac boxes and other assorted rubbish. But it’s there, amid the general detritus of Star’s life, that we squeeze in between Star and Erin, and a random stray dog, and join them on their hero’s journey.

*

In essa’s endorsement for Poorhara, they say Michelle’s characters are so stunningly well-realised they will walk into your dreams at night. And if I had to come away from Poorhara with just one lasting impression, it would be this. As the road unfurls before Star and Erin, as the Mira’s odometer creeps up towards what I can only assume must be the 300,000k mark, we are their privileged observers. Rich and unrelenting, heartbreaking and hilarious, their internal worlds are as expansive and ambitious as the land around them, and as turbulent and hot as the roiling atua beneath. But the true beauty lies in what is spoken—truly some of the best dialogue I’ve ever read—and in what is shared. In who they are together.

It goes without saying that the concept of home has a powerful presence in Poorhara. And over the course of a book Erin and Star will show us that it doesn’t necessarily exist on Google Maps. The cousins have run from their family home in search of their whenua and, in the inbetween, found temporary lodging in Star’s broken little car. But how long and how far can one 1994 Daihatsu Mira with a cassette-tape auxiliary adaptor actually go? Poorhara will show us that when the tread of a tyre is replaced by footprints in the earth, when the dying roar of a motor becomes the sound of two hearts beating, we are closer to home than we realise.

*

Ruuaumoko saves his most spectacular display for the final chapters of Poorhara. And in the aftermath, as the world begins to cool, we see Star and Erin’s landscape has shifted again. We realise that, of Ruuaumoko’s two diverging fates, perhaps both things can be true: one can be caught while also being loved. The fire that breaks the surface is also the one that brings us warmth, and no good change comes about without agitation. Most importantly, rumblings are a sign of life, presence, communication and connection. And if we’re allowing room for multiple truths, it might be worth acknowledging the third version of Ruuaumoko’s story, which has him still in utero when his parents were separated. He exists as boundless potential, in the most tapu state of all.

A closing thought: the final chapter in Poorhara is called ‘Ka Puta’, which means to appear, escape, get out, survive, or be born. Which might be unrelated. But it’s something to ponder.

With that, I’m now going to pivot, with the grace and agility of a bald-tyred Daihatsu, back to the thing that definitely is appearing, getting out or being born this evening.

And so, please raise your glasses in celebration of this phenomenal book. To Poorhara, to Star and Erin, to the tuupuna who walk before us, the atua who hum beneath us, and the stories that sit within us. To Michelle, and your absolute, explosive brilliance. Thank you. You’re the reason we all keep going.

Mauri ora e te whaanau.

Michelle signing books after her launch

children of the knots

rattling kids shaken in the belly of a dead fish

picking little bits of life out from under the fingernails

to make a mosaic of families

that tied knots too easy to loosen

letting everything else get twisted up

in the process

domestic settings gone nuclear

the nut cracked open

swallow it in one gulp

these kids know about digestion

they’ve been chewed up for so long

converting whatever they have left

into energy enough

to build a tower out of knots

the really hard ones that don’t budge

just give up tender little threads

these kids know that so much can hang off

such tanglings

and what falls into hot sand or molten dirt

is retrievable

if u r not afraid of getting burnt

—essa may ranapiri

Tenei te poo-hara

Poo

Two meanings; one, is Night

A Hidden time, not necessarily a feared time as in four-legged places.

But neither is it always a time-place of creation and rest in the same breath.

Two: is Poo

In the way our streets speak

Poo

Means not enough

Means make do

Means number-eight wire some money from somebody then buy a pack of buns and a 1/2 chicken and maybe some coleslaw, nah, too much.

Loaves and fishes eat your heart out kahi ma, we got buns and off brand k fry, got that dollar-store eyeliner looking finger-licking good

Then comes:

Hara,

mistake, foul, offence.

A kaumātua taught me this one, she’d say to me, 'Hine, You can’t be going out in the streets looking hara, you’re representing te ao Māori, go outside and brush your hair.'

I said ae ra nan, and I went outside as i was told

Inside my mind I knew I’d never not be hara, never not be poohara

Inside my mind I said, I got mad girl hair, I got a pig dog face, I got crazy eyes and a

a snot nose, e rere ana te hupe ia ra ia ra no te hiku o te mauka ki te moana

Ko au he poohara, ko poohara ko au

Ko poohara ko mātou, Ko mātou te iwi o poohara

Tenei te pukapuka o te iwi nei

Poohara, nau mai haere ki te ao o te pukapuka nei.

And every book has ancestors

This book is no exception

Māui is stoked to be here

Every protective factor he can find in one room

Every threat turned to a joke

Every joke turned to a threat

Until the sun has slowed down to a sizzle.

James Joyce is here,

ready for the journey he has already begun and finished

Beckett is outside with his hands in his pockets

Just waitin' for a mate

Keri couldn’t be here, it’s whitebaiting season up in heaven

Which up there, is every single day.

There are tohunga, there are rangatira

There are aunties, mean ones, and mean it ones

Captain Cook is an ancestor too

We bring him in

Give him a kai before he becomes one

He can learn the hard way why the hakari is only noodukz and 99c fizz

You can put a lot of love into a bowl of two-minute noodles

Two minutes is a long time when you’re not going anywhere

Nah not going anywhere eh

This book is for the cousin who who was told to shut up when they talked about it

This book is for the cousin who talked about it anyway

This book is for the cousin who shut up about it too, its hard to know what rules to follow when you’re not big enough to swim on your own down at the bridge

This book is for the cousins who survived hard enough to become girlbosses

Who come home at night to deal with all the whanau dramas they will never be able to run from. Each night like

licking the icing off a big burnt cake

This book is for the cousins we lost along the way

It’s for the crosses on the highway

It's for the windmills that never stop.

This book is for the cuzzys who put on polite city Māori voices

Only to turn them off after their second ciggy out on the porch with the sis from ngongy

This book is for the cousin who says, 'Far g, have you read Mary Shelley? Oh na, Kafka? Faaa shit’s buzzy'

This book is for the Pākehā cousin

Well it’s not for them, but they should read it.

Because we might be from the streets that the sulphur burnt we are fucking brilliant

There’s nuance to our aesthetics, state house Victoriana with a twist of French we don’t speak. You wouldn’t get it kare, lest you grew up like me.

He kai kei aku ringa

While you clap in the gaudy halls of plastic maoridom

We girlies go shopping for free

This book is for the cousin who can’t read because they had to look after the kids

This book is for the cousin who read to you when the grown ups were in the shed.

This book is for the cousin who became the grown ups in the shed

This is the book for the aunty who built the shed that housed the uncles that sung red red wine while she looked after their goddamn tamafreakies by chucking on the animated classic ‘Country Mouse and City Mouse’ in the lounge with nothing but a bunch of mattresses for company.

This book is for the ones who couldn't take it anymore

But instead of leaving us completely

They got in the car and kept driving and driving until they got pulled over on their own land

for not having the right pieces of paper to allow them to run from it

—Ruby Solly

Poorhara (paperback, $38), is out now at Unity Books, all other good bookstores, and here on our website.