'Normally in a situation like this I would try and be funny': Launching PLASTIC by Stacey Teague

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 27th Mar 2024

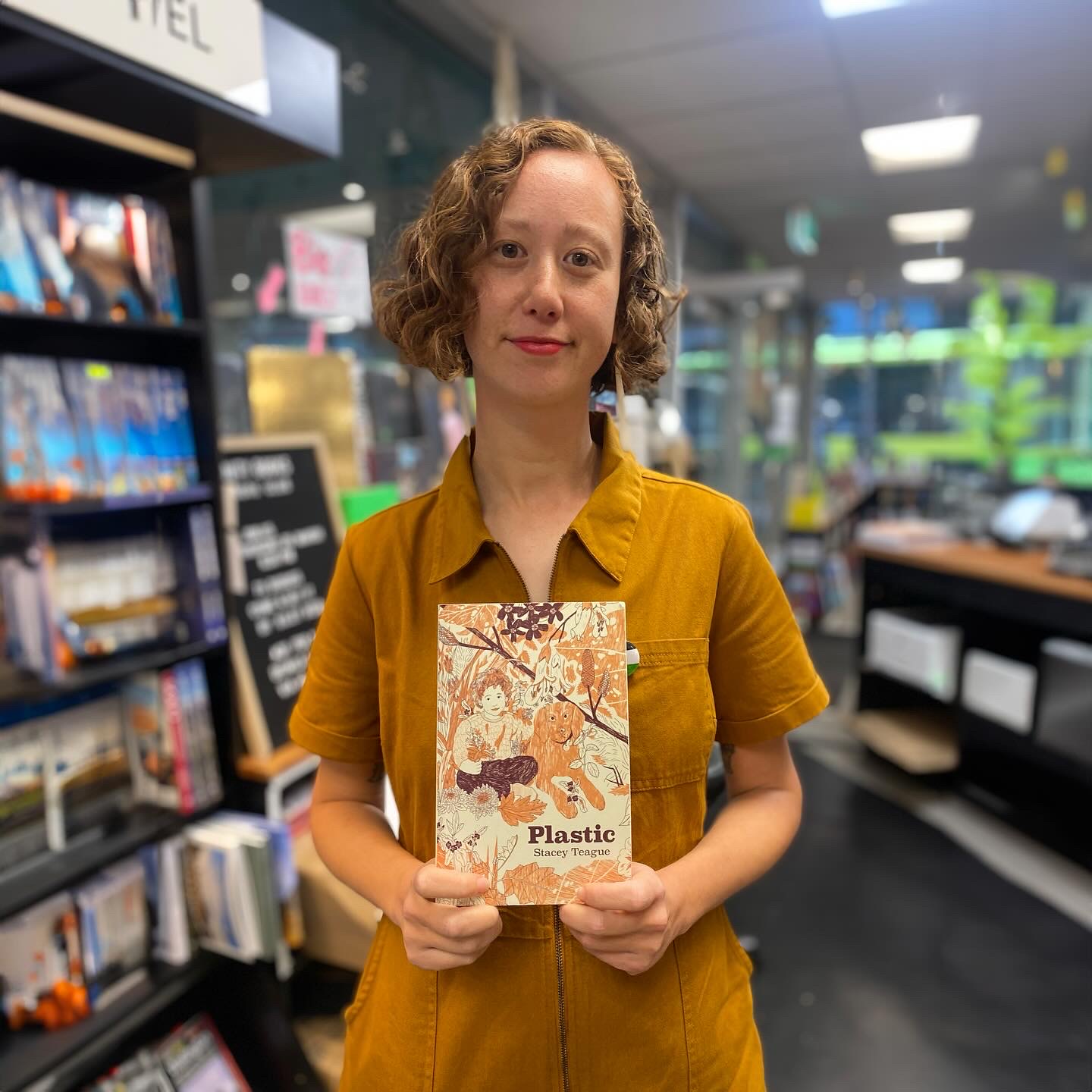

On 14 March we launched Stacey Teague's new poetry collection, Plastic, at Unity Books Wellington. Thanks to everyone who came along, and thanks Unity for hosting us.

With us to launch Stacey's book into the world were novelist Rebecca K Reilly and poet and publisher Ash Davida Jane. Their speeches were works of art in themselves so we have reproduced them below.

Rebecca:

I am here to take up the role of 21st style speechmaker—often people get their dads to do their 21st speech but if you are a 34-year-old author it makes more sense to get an author peer to do it, and so I am here today as the only other person in our group chat who has ever finished writing a manuscript and also the only other person from Stacey’s hometown of the former Waitākere City. Stacey asked for this speech to be a roast but one time she did a 'how sensitive are you' test and got 100% so I am not going to go that hard on the roast aspect.

I first met Stacey in 2019 when we were both on what was at the time being described as the conveyor belt for conventionally attractive young women to be published by THWUP, i.e. in the MA programme at the IIML. I already knew who she was though, because she was kind of big on the blog scene in 2010.

We were not in the same class—Stacey’s class was all about community and being respectful to each other, and my class was all about suggesting each other write totally different books and arguing about whether it’s fair enough to narc on your own children to the police. Stacey walked straight up to me in the IIML library and offered me a ride to the Māori writer’s hui, which I accepted and then she missed the motorway exit to Porirua both days. We went to a workshop for new writers where we were supposed to go around and say our names and one thing we were the author of, but that took the whole hour because all the aunties got into the whole situation of why their names were what they were and who’d gone down to register them at Births, Deaths and Marriages. Most people said they were the authors of Facebook statuses but they wanted to take things to the next level, and then Stacey said she had actually published a book already, which I actually didn’t know until that moment.

I think it’s very special to publish a second book—the first book is where you figure out if you can write a book and the second is where you have to show the people who you actually are when you’re not just figuring things out, which is a lot more difficult. I also think that it’s admirable not to rush out a second collection as soon as you have enough poems to do so. A lot of publishing is being patient waiting for other people to do things that you have no control over, but you also need to be patient with yourself and your writing, even though it can feel like you’re stuck in the shitty and infantilised new-emerging writing phase because you don’t have a second book, and you don’t get invited to anything because you’re not part of the zeitgeist. Stacey possesses this patience as well as a groundedness, which is something I feel can’t be learned.

After the hui, Stacey invited me to see Jojo Rabbit, and for some reason, probably because she is a charming and compelling person, I went even though I had seen it, like, two days before, and I had not written the last third of my manuscript, which was due a couple of weeks later. To this day, nearly five years after this, people are giving their two-cents to the last few chapters of my book seeming rushed and to that I would have to say, well it was because I needed to go to the movies, and it was worth it to seal the deal with this lasting friendship with a woman who pulled a whole box of Shapes out of her tote bag in that cinema.

Ash:

For those of you who don’t know me, my name is Ash. I’ve known Stacey since we started our Masters in Creative Writing together in March 2019, which means I’ve seen this book grow through its full life cycle, and I feel very strongly about it. It’s a real honour to help launch it.

Normally in a situation like this I would try and be funny but given I’m following the author of one of New Zealand’s funniest novels, I’m going to lean the other way and embrace my own niche of being overly earnest and probably crying.

Stace and I have had lots of conversations about the point of publishing a book, which is ironic if you know that we own and run a publishing press together, but we’ve often ended up at the answer that it’s just a good excuse to have a big party. I still think this is a perfectly good reason, but the other secret reason I never said is that now I get to stand up here and say nice things about her and she has to listen.

Stacey’s poems are very generous in how much they let us see, particularly in the small moments that often belong only to one or two people, like a little forehead kiss in line at a medium-tier rural café, or even the inexplicable shame you feel when a family member passes. She has put so much of herself in Plastic, not directly, but in reading it you can sense the shape of a whole life.

This book is the result of a lot of hard work, meaning the writing but also Stacey’s work of tracing her whakapapa and finding ways to reconnect, which includes having the difficult conversations with her family about it, and looking her discomfort in the eye. That work is part of Plastic, in that the processes of unfolding the layers and of the writing itself are present in the book, but Plastic is also a part of that work in itself, and it’s beautiful to see it in the world and to know that the people who need this book will be able to find it. You can feel the care that Stace has put into this collection. When I read the poem ‘spell to survive’ I always pause at the line ‘Today I turned 31 and felt each of my years like a multi-tiered wedding cake’, to imagine all the time and love it takes to stack and ice all 31 layers of that cake, each layer so perfectly finished. That cake is like how I see Plastic, with so much attention to detail given to each poem, each one a whole and finished thing in itself but when you put them together they fit perfectly.

Plastic is also full of spells, to sate or solve almost any problem from healing an unseen wound, to falling in love, to overcoming distance and I do think rereading these poems whenever something is wrong in your life will help. This book has such a calm, grounding, assured energy, which is the same energy Stacey brings to the lives of the people around her—most of the time.

Plastic is also full of women, from Mary Oliver and Sappho to Anahera Gildea and Talia Marshall, to Stacey’s tūpuna wāhine, to Hilma af Klint, to a series of ātua wāhine who speak to and through the poet. The last poem in the book, ‘spell for nowhere’, opens with the line ‘world of sisters’, which is what Plastic is, right from the lyric essay that opens the book, where Stacey’s sister welcomes her home with the spare room already made up for her, and looking back, cuts her hair with kitchen scissors or straightens it with the iron, or watches their favourite movies together—Twister, Empire Records, The Mummy, and Hackers. In this world, sisters, whether related by blood or not, are anchors. And as people read Plastic, I think many of them will have that same feeling of having found a new anchor, a voice to return to again and again, for inspiration or courage, or to feel grounded.

I

toyed with the idea of buying a bottle of champagne to smash against the book

and officially launch it but I didn’t think Unity would be very happy with me

and I also wasn’t sure I could pass it off as a business expense to the IRD, so

instead I’ll just say congratulations.

Plastic is out now! (Paperback, $30.) Available from Unity Books and all other good bookstores, and here on our website.