Maybe her life had begun again: Launching Root Leaf Flower Fruit by Bill Nelson

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 22nd Sep 2023

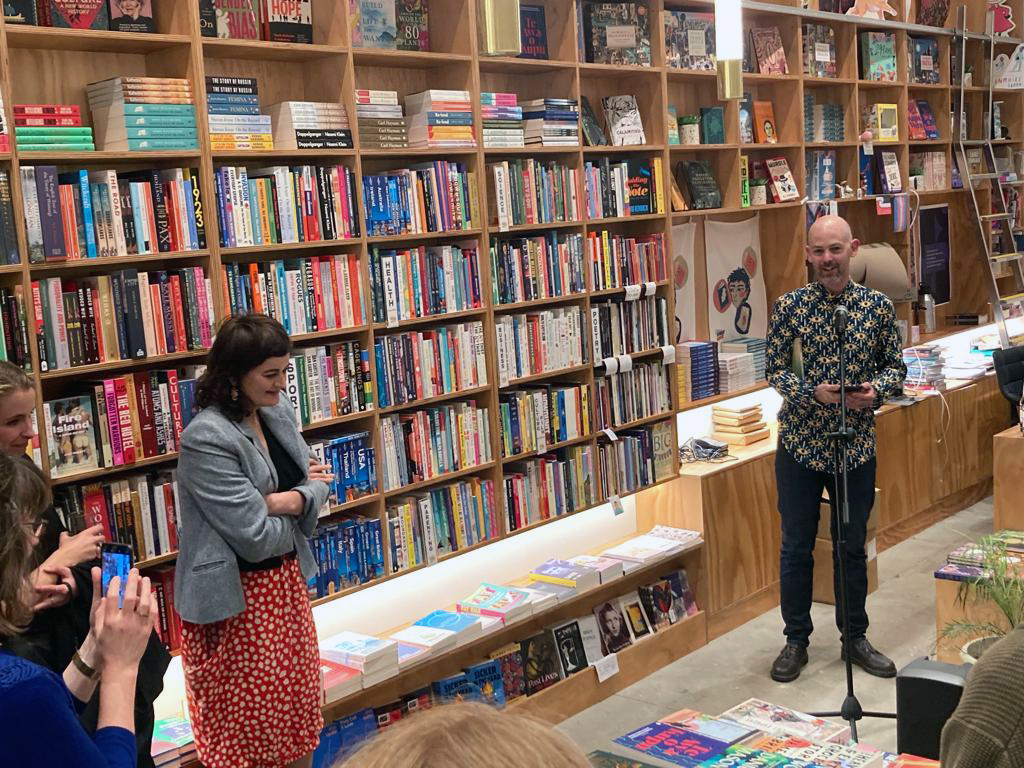

On Thursday 21 September we launched Bill Nelson's new book, a verse novel, Root Leaf Flower Fruit. Hooray to Bill, and thanks to everyone who came along to celebrate. Many thanks as well to Good Books, who hosted us.

Bill's editor, Ashleigh Young, said a bit about the book. Her speech is below.

Thank you everyone for coming to celebrate this amazing new book by Bill. I met Bill nearly 15 years ago, in our MA year at the IIML, and it’s a privilege to be helping to launch his second book today, after the excellent Memorandum of Understanding in 2015.

First of all, who among us is writing a verse novel, in this economy? I mean obviously lots of people are – there’s Ruby Solly and essa may ranapiri and Airini Beautrais, Anne Kennedy, John Newton. But why, why are they doing it? I keep hearing that this is the most challenging, the most off-putting of the poetic forms, the form that has no mercy on the reader. The reader must work. The poet who writes a verse novel must be ready to defend themselves at all times, ready to answer the question Why this? Why now? How dare you? (These are all things people are saying, not me, by the way.)

My take is that all of this is beside the point. Root Leaf Flower Fruit is a great book that happens to be a verse novel. It’s for the reader who wants to be absorbed, transported, consoled. It’s a book that opens itself up to us line by line; a book that disorients then clarifies then disorients again. It’s about how a person’s struggle to clamber out of a mess can be rich with discovery, and beautiful hats, and figuring out how to start a tractor. It reveals that sometimes when our defences are at their lowest – when we’re ill or recovering, or even near death – the truth can shine through us, or maybe we’re more open to finding it. As Bill writes: how consciousness is an open question, / a thing still flowering. There is such mystery and thrill in this book, and you can see that thrill unfolding in the writer as well, as if he’s breaking into a gallop.

The story goes something like: a young man wakes up from an accident, mud in his mouth, his fingernails, his ears. The world feels different and he can’t say in what way. He’s fallen off his bike and hit his head badly. After a recovery of sorts – though, as with all head injuries it’s uncertain how long recovery will really take – he tries to go back to work, where he’s a physicist studying hydrogen molecules in deep space. But his project funding is about to come to end, and the opportunity comes up to go to his grandparents’ farm. His grandfather has just died, and his grandmother has had another stroke and is in a care facility. They had owned a biodynamic farm on a place called Aka Aka Road, with old pine trees nearby and a creek full of watercress and eels, and where the earth is depleted but restorable. So, the young man’s task will be to get the property ready for sale. He decides to leave his job, hoping to get his old self back, and throws himself into this project.

Just a side note here: there is something deeply satisfying to me, in a shallow makeover-show type way, of watching this guy get to work.

I’ll work

outwards – start in the hallway, then the dining room;

I’ll throw

away the fishing magazines, the piles

of old

newspapers, some published

before I was

born. I’ll scrub the kitchen,

dust the

lounge.

. . .

And I’ll

water-blast the mould from the verandah,

trim the

lawn, tidy the flower beds

and prune

the trees, rake the stones in the driveway

and pluck

weeds out with my fingers, tidy the garage,

remove the

junk and old tyres from the rafters.

This list of tasks is completely compelling to me, a bit like those old infomercials where someone demonstrates the power of a vacuum cleaner against different violently spilled materials. Just hook it to my veins!

At the farm our young man finds the diaries of his grandmother, from the time before she had her first stroke, and it’s here that she begins to come in and out of focus for him. We learn about her marriage to this young man’s grandfather and their effort to grow things, ‘planting by the phases of the moon and the constellations, making everything by hand’. Her days are 'long and overlapping, like woven flax, like a mat, like a basket’. There is a great deal that the young man and his grandmother don’t know about each other, and her mysterious third-person voice and her grandson’s candid first-person voice become entwined in a kind of dance, one building in strength and colour as it is given space. The grandmother’s voice on the page is described as ‘sentences rushing into each other, chooks rushing in for a feed’. My feeling about this character is that, even though we know she is near death after her stroke, she has been waiting all this time, as if under the soil, to surge forth.

The book acknowledges the sadness of never being able to know everything about another person’s life and inner workings, but beyond that sadness, there is a kind of wild freedom and grace.

Maybe her life had begun again.

Maybe she had left us behind, a side step

to the left, maybe she was free,

freer than she’d ever been

to do, to say

whatever she felt like.

There is this almost unbearably poignant suggestion in the book that sometimes what we think is the last time we have seen somebody isn’t the last time. Sometimes there’s the last last time, then the last last last time. Then we find them again.

As it happens, a verse novel is exactly the right form for this book. In these lines we watch this man re-learning how to be in the world, step by step. We see him loping through the neighbourhood on ‘alternating feet’. We feel the steady churn of time – the persistence of the seasons and the inevitability of decay. The form itself takes measured steps, but begins to bend and quicken its pace, and finally it breaks into something new and breathless as the grandmother takes centre stage, setting out on a fearful but determined walk in her Postie catalogue heels and apricot-coloured earrings, her life telescoping into the distance as she follows the steepening and flattening road.

There’s an image of a bottle thrown from a car window at a young man while he is out on a night walk: the bottle seems to transform from a random projectile into something almost beautiful, like a satellite, then a kind of flower, then diamonds. And in another moment, our young man discovers his grandmother’s hats: what once might have held just a passing interest is suddenly irresistible, pulsating with beauty and possibility. This is a book about transformation, both sudden and slow – transformation that people strive for, but also transformation that presents itself like a question.

It's very difficult to describe this book, as you can see. I think of it as a book of questions, beautifully

asked and explored. They are questions that take hold of us, like: ‘What is going on

inside another person’s brain?’ ‘What is going on in my brain?’ And, of course,

what if when you don’t feel like yourself, you’re really not yourself anymore?

What if you could become someone else – even if only in somebody else’s

imagination?’

Photo: Morgan Bach

Root Leaf Flower Fruit ($30, paperback) is out now from Good Books and all other good bookshops. Also available here on our website.