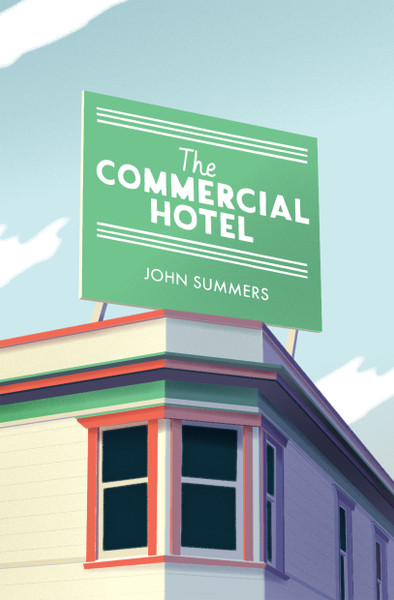

'Like a quiet dad but one with incredible communicative powers': Launching The Commercial Hotel by John Summers

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 16th Jul 2021

We launched a marvellous new book, The Commercial Hotel by John Summers, at Unity Books Wellington on 15 July. Here's what our editor Ashleigh Young had to say about it.

Sometimes I think that the harder a book is to describe, the more interesting it is. But not being able to describe a book won’t help to sell it. I wish it could just be like: ‘What’s it about? ‘Oh, well, I can’t explain it.’ ‘Sold!’ But no. I need to try to tell you what this book is about.

The other day John and I were emailing about Kim Hill, as he is being interviewed by her soon. And I remembered a terrible moment in an interview with her when she asked me what an essay was. I can’t remember what I was thinking, but I was possessed by some insanity and said, ‘Well, I think a better question is, what do essayists do?’ And she said, ‘Very well Ashleigh, what do essayists DO?’ I have been withering and dying ever since that moment. Maybe I only said it because I didn’t want to talk about Montaigne anymore. But then I thought, maybe my moment of lifelong shame could, somehow, be useful after all. Maybe the question is less ‘What is the book about?’ – because there are many subjects that The Commercial Hotel addresses, many deep dives and set pieces – and more: ‘What is John doing as a writer?’

Because John is the kind of writer I would eagerly read on any subject at all. He’s kind of like the night train. I don’t care where it’s going, I’m getting on.

To be clear, I love what he has written about in this book. ‘Searching for an idea is like resolving to have a dream,’ the essayist Hilton Als has said, and this book feels effortless in its having of ideas, as if John had only to turn over a log and find all the life secretly teeming there. We get the story of his grandmother, Connie, who was dragged by police off a butter box where she stood giving a speech protesting World War II. The story of his grandfather, who ran the infamous John Summers Bookshop in Christchurch, which became the supplier of New Zealand poetry to the State University of New York. John isn’t a writer who is determined to convince us that the ordinary is in fact extraordinary. He’s a writer who can reveal to us the value, the weight and the heft, of the ordinary furniture and concrete detail of our lives.

‘I could think serious things about books and life even if I was cooking my noodles in a shared kitchen,’ he writes in an essay on reading James Joyce in between picking apples. ‘Epiphanies might happen on the banks of the Clutha.’ Ordinary things have ghosts, and auras; they touch some ancient nerve in us. In one essay he remembers reading a book on ghost-hunting, which suggested that the ghost-hunter carry a carpet bag for lugging the gear. ‘As a result, for the longest time, the words "carpet bag" carried an aura, they hinted at the dark mysteries of the occult.’

But maybe, maybe even more than what he writes about, I love the way he’s written it. His delight in words like ‘carpet bag’, and ‘huarache sandals’. His honesty, his surprising and true observations, his getting at the feelings of Sunday afternoon dread that the wistful jazz flute of a TV theme song can summon in us. The way he notices the particular structure of a telling off from a schoolteacher: how the teacher tells you all off as a group, then as individuals, then turns back to the group as a whole. John’s essays, like all good essays, live in their details.

As a narrator John is both intrepid and deeply fearful, which is everything I personally want in a narrator: someone who’ll put themselves on the line for the sake of the story, and someone who is very afraid of embarrassing themselves. Someone who’ll set out with a guidebook, then have to drive slowly back down the street looking for it after leaving it on the roof of the car. We get to know his past selves. He is a traveller, a young boy fearful of the future, a student going tramping ill-prepared, a reader, a daydreamer of course. And we get to know his way of seeing, as if he has fashioned himself into a very tiny ‘You Are Here’ pin on a vast map.

From the edge of the universe where he lives like everybody else, he turns to what is falling off that edge and disappearing. Like dungarees. Like forestry towns and freezing works and beer by the jug. Then there is what has already disappeared – like accidentally deleted computer games, or the job of running a theology section in a bookshop. When he writes of people such as Simon, an acquaintance who entered his life briefly and brightly before going missing, he thinks of how Simon made him feel a part of something bigger. How his disappearance made the world feel less knowable. So much loss is like that – it casts us adrift, like the world itself is shrugging us off at the very the moment we thought we had purchase. You can read this book as John trying to seek out new footholds in this place, even as he has one foot stretching back into the past, even as he’s reading ghost stories. And part of that is paying attention to what we still have now, but that we maybe don’t think is worthy of thoughtful attention. John manages to convey a deep reverence, love almost, for things like the dump, and Elvis impersonators, and Arcoroc mugs, without ever quite saying it directly, like a quiet dad but one with incredible communicative powers. It’s an instinctive love he has, a bit like the words ‘night train’ and the way they hold such promise, even magic.

For me, one of the many pleasures of this book is John’s sensitivity to social discomfort. Some of these discomforts are oddly formative, like a granddad reciting a poem about a polar bear and suddenly, terrifyingly, hitting top volume for just one line, or being on school camp and feeling anxious about falling out of the top bunk, because he’d heard a horror story about someone doing that and biting their own lips off. Or the memory of how greeting a particular grandparent with the word ‘Hi’ felt too casual, felt moronic even. All of these moments of not quite belonging, and at the same time sensing there is some way of doing things that you are meant to figure out on your own without being told, like maths in standard three. John captures a silence and withholding that I think is particular to New Zealanders of a certain generation, but he also captures our weird flamboyance and occasional refusal to follow social conventions, like an aunt who mimics accents, or a classmate who eats Blu-Tak.

Then there’s Bernard Shapiro, the desert adventurer in his pith helmet and tattered Edwardian moustache, posing for a photo on the bonnet of his jeep, pipe in hand, or struggling across a swift-flowing river in his antique outfit. What are we to make of this guy? ‘At one point I had warned him that nothing might come of our conversation,’ John writes of Shapiro. ‘I couldn’t say for sure that I’d be able to write anything but had simply come to see him with notebook in hand, chasing something that had struck me as curious. "It doesn’t matter," he said, and I realised immediately that if anyone understood, he would.’

This spoke to me of the way writers helplessly approach our

ideas, uncertain if anything will ever come of them, eventually getting so

far into it that we just have to stay the course.

John is so good a writer that he can have it both ways: Nothing comes of it, and everything comes of it. It doesn’t matter. Because through the way he pays attention – humble, hospitable, uncertain, dreaming all at once – he makes each of his encounters with the world electric.

The Commercial Hotel (paperback, NZ$30) is available at all good bookshops and from our website.