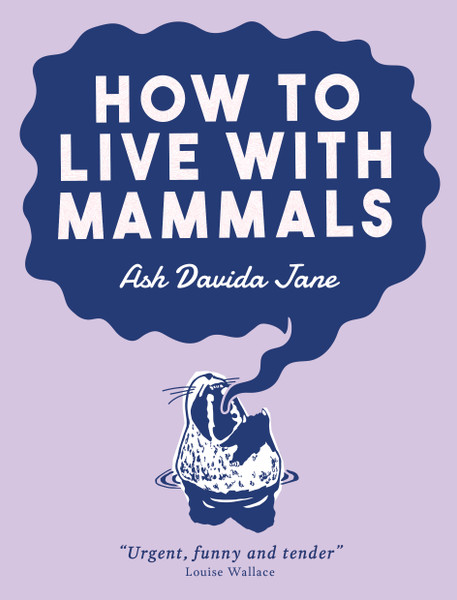

Launching How to Live with Mammals by Ash Davida Jane

Posted by Pip Adam on 28th Apr 2021

We recently launched Ash Davida Jane's fantastic debut poetry collection, How to Live with Mammals, at Unity Books Wellington. We were really happy to have Pip Adam there to launch the book for us. Below is Pip's speech. Thank you to everyone who came along to celebrate.

*

It’s appropriate, perhaps especially for this book, but at all times, to acknowledge the land we are on. The violence that has been enacted on it, the trauma it holds and the timelessness of its history, presence and future. It’s also appropriate to acknowledge the mana whenua of the land we are standing on, Te Ātiawa/Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika, and their guardianship and care of this land especially during this time of colonisation and in response to the harm this has caused.

The land has been here for a long time and will be here long after we are gone. Ash Davida Jane’s breathtaking book How to Live with Mammals understands this to its core. There is a constant reminder of times outside our own. In ‘Transplanting for Dorothy Wordsworth', the speaker of the poem reminds us ‘it takes more than one human lifetime for a forest to grow’.

This book re-aligns minds. I challenge anyone to read it and not be changed, not to look around, like a traveller to another dimension returned, with a new sense of our interconnectedness and a slight, aching horror at the damage caused by our delusion of independence.

One of the realignments it makes is the de-centering of the human animal. This collapsing of humans into the world around them allows for a reinvention of everything we do – love, eat, garden, name. All the things we take for granted are made strange through incredible control of language, image and point of view.

In ‘good people’ the speaker addresses a Tetra Pak:

o soy milk carton I just want to recycle you I just want

you to go on and fulfil your life dreams

of being pulped

& reused to make new cartons

and hold other consumable liquids like orange juice or almond milk

except we can’t call almond milk

almond milk anymore

because it’s too misleading & causes innocent shoppers to

imagine almonds with tiny almond teats being milked by

almond farmers who get up at 4am everyday

nobody wants to think about that while they do

their grocery shopping

But, of course, now we can’t but think about that while we do our grocery shopping. The poem has changed us. It’s got inside our minds and broken that part which can pick up a Tetra Pak unthinkingly. The bit that allows us to eat without regards to the source of the food we eat. We will forever be thinking about those tiny almond cows – the humour of the image that allows the surrender and openness of a laugh to make us think about the water it takes to grow the almonds and to look further, perhaps, to the cow shed, where the other milked population work.

This precision of and play with language is often utilised to challenge language itself.

The poem ‘taxonomic loss’ begins:

I call a body a body / I call a name but the named thing has

vanished / grey whales / from the Atlantic / their name

meaningless to them / salt water rushes to fill the absence /

how easily language dissolves / a voice decanted / to know

and to name are different urges / to go about the day feeling

mammalian / to

feel the sky on my back / see the atmosphere

as a tent / and let that be enough /

And this is part of the machinery of the work. The

breakdown of language to break down our sense of the order of things. This act

of re-arrangement goes further than just our position in the taxonomy of living

things. Some revolutions are loud and violent, and some are beautiful and full

of love, peace and joy.

I’m thinking in particular of the environmental activism Joan Fleming is involved in at the moment in Australia.

Joan wrote recently, in a post attached to a photo of herself in amongst brightly dressed dancers, ‘Somehow we pulled off an epic week of actions in Naarm/Melbourne, capped off by Civil Disco-bedience, now a non-violent direct action classic. We want system change. We want appropriate policies in the face of this terrifying ecological and social justice crisis. We want government at every level to tell the truth. Until that happens, we will keep dancing against the death machine.’

And this seems like the spirit of Ash’s work in this book. It is a book that catches the planet at a moment of crisis and transformation and when it catches it it is curious, not maudlin. There is a realistic hope in the work. A hope that comes from perhaps the only place hope can – despair and action.

From ‘umbilical’:

if you have held in your palm a fish drowning in the open air

or swum deep underwater felt the pressure build in your ears

and brain you know how bodies can change

It catches a moment alive and fecund but also disappearing before our eyes, slipping through our fingers. It describes love in the time of the climate emergency.

And in ‘undergrowth’:

nobody’s been here for centuries

most of the birds are gone too

but an ant crawls

across the cracked marble

& somewhere in the silence our buried

forms turning

back into earth are still

in love

It has this amazing ability to see not only the effect of the Anthropocene on the planet but by pulling us back into the animal/mammalian world it very clearly describes the effect of the Anthropocene on us. There is an amazing conversation, an equalising effect to the book, a speaking ‘with’ rather than a speaking ‘to’. This odd sense that the mammals are us and everything else in the world is being forced into the urgent job of learning how to live with us. And, seeing this, I couldn’t help but challenge myself to do better.

I just want to end by giving Ash the last word and leaving you with the opening image of the last poem, ‘extant’. With these words, I want to thank Ash so much for the opportunity to read and think and speak about this amazing book, to urge you to buy this book and, as with any magic spell, with the speaking of these words, the book is launched into the world it captures so well.

i wake in the night with phantom pains

in the limbs of lost species / first,

the avian twinge deep in the scapula,

spine curved forward, shoulders drawn up

and elbows folded in / turning away

from the ground / the subconscious responds

with recurring dreams of flight /

How to Live with Mammals by Ash Davida Jane is available from our website and good bookstores.