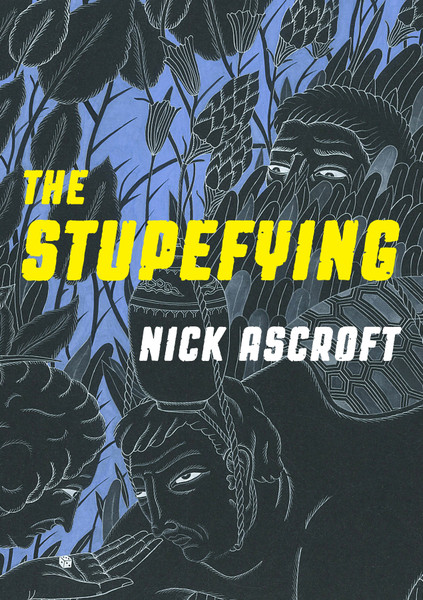

Dismantling the croquembouche: Launching The Stupefying by Nick Ascroft

Posted by Ashleigh Young on 27th Sep 2022

On Thursday 15 September we launched The Stupefying, a new poetry collection by Nick Ascroft, at the rowdy Hudson.

Poet (and recent winner of the Best International First Collection from the

Laurel Prize 2022, with her collection

Meat Lovers!) Rebecca Hawkes

delivered the following searing speech.

No poem shimmers. No writing is luminous.

It’s black text on an off-white background.

If you see any shimmering or luminosity,

you have a migraine.

The poem goes on:

What I think we’ve got is sugarwork.

Luminous means good. Shimmering just

means good.

Fellas, the book is . . . good.

It’s anyone’s guess as to why Nick, so suspicious of poetical excess, has engaged me – fruitiest and most diaphanous of maximalists – to spin sugarwork for his launch. But there we have it. Whatever extra candyfloss I fluff up for the next five minutes, know this: The book is good.

That’s why we’re here. That and whatever dubious loyalties oblige people to attend poetry events…….. but let’s not peel that onion. Instead let’s peel this onion, this delightful and alarming and original and heart-twanging and bold and hilarious book, The Stupefying.

From the get-go, even before we get to the puncturing of the whole luminosity delusion, this book chucks stones in the fragile glasshouse of poetry itself. The collection opens with a poem that (among other gut-punches) skewers ‘the arts’ as ‘self-aggrandising, deceitful, flavourless’. This is a poem that I first met when Nick intoned it at a poetic Requiem Mass among the ornate fretwork at Saint Peter’s with an original musical accompaniment, which I suggest is not the activity of someone who wholeheartedly backs this accusation – but isn’t it satisfying to hear someone say it, in print on the radiant page? And then, even better, hear that someone ultimately making a cracking case for the enduring solace of art, whistling the tolerable bit of Madame Butterfly in the void? Nick’s poems shimmy along the precipice of the abyss, taking nothing for granted – from the inherent merits of artistic pursuit, to something as mundane as the softness of a therapist’s chair or their anachronistic glass ornament.

Then consider this extract, absolutely nuking every flirtatious poet in this city in one fell swoop, from ‘Poem for Derek’:

Why does anyone have a poem aimed at them

is the question.

Answer: to get into their pants.

As if a poem wouldn’t have

the absolute opposite effect.

And what sort of pants might a poem provide access

into? Not any pants you should

wish to find yourself in, Derek.

Only the most despicable pants, which

once inside, one might howl and attempt exit from

at all costs and rapidly.

Only Nick can deliver these devastating smackdowns of poetry in a poem and get away with it, because nobody is more acutely critical of art than someone who takes it really seriously.

Nick is, as far as I’m concerned, the country’s master craftsman of verse, evidently revelling in the thrills of the skill in several pages of perfect ottava rima, and turning his hand to forms from collaged limerick to sonnets in iambic pentameter. Not just anyone could rhyme lockdown with ‘write some schlock down’. Nor would we want them to. But Nick knows all the words there are, or at least all the words that can be tactically deployed in Scrabble, plus the heated politics thereof.

In the poems you can sense the undercurrent of his inquisitive, calculating braininess, gathering language to brandish at the most strategic opportunity – ‘the liminal marshmallow of the mind’, the entire bewilderment of 'Pishy-Caca . . .', the astounding semi-found (recycled?) ‘Therefore We Commit This Body to the Ground’:

Dust to dust. Aluminium to aluminium.

Polypropylene plastic with a little 5 debossed

inside a triangular uroborus to something else,

ideally, yes, another form of thermoplastic

but we don’t have the facilities at the present time.

Nick as the comedian of The Stupefying claims to be ‘not funny ha ha, more funny hmmm’, but he certainly made me bark aloud in mirth throughout the book. Several of The Stupefying’s poems take on the voice of a chummy curmudgeon – at its extreme a bombastic great-grandad ranting over current affairs. Other poems take on personas of a vulgar silver vixen, a wealthy wearer of white pants, and even a visiting entity that materialised for a time as an art installation of techno-tentacles muttering above the Left Bank arcade. Always, Nick’s poems are loaded with a blistering wit that bubbles to the surface . . . even as his more directly autobiographical narrative character gets the stuffing knocked out of him or, worse, demands that you picture him in shorts.

The picture Nick paints of himself in this book is largely of a terrible cyclist. He must be a menace on the road. The cyclist-poet is all skinned knees and yoinked joints, thumbs wrenched from the brakes, skull concussed in factual and fanciful brain injuries. My question is: where is this guy’s helmet? But this book is filled with all the aches and spills of life, from a wild-haired wasp-stung misfit kid, to a young man balancing bravado and hesitancy in Japan, to a dad and ex-husband navigating new terminologies of custody and rapport.

As one poem reports,

The blows

come. From the left – WHAM – the right – SMACK – from

below into the groinal area. Some I invent. Some I

overindulge. Some I blank. I’m okay. I am okay.

Some of the most profound poems from the book navigate the OOMPHs of the author’s recent separation, but while the poet is going thru it, it’s not giving ‘not coping at the open mic’. Wise indeed is the poet who feels the twang of some unnameable heartstring but won’t strum it too bloody in public. Still, the poems that draw from the harrowings of real life strike heart-achingly true, as two people ‘push at despair like wrists against dough’, but no bile is spilt. Maybe Nick is once again trying to charm us with his reasonableness, like a room full of couple’s therapists from that excellent poem up on Newsroom this week. But like much of Nick's best work, the poems are unsanctimonious, witty, deeply humane comments on the compromises that comprise life . . . the bargains we make with ourselves, each other, and our egos or neuroses to get through the day.

As well as marking birthdays, anniversaries, and the adjustments of the new arrangement, the book reaches more widely to the author’s deep and enduring friendships. After a poem dedicated to Kate at thirty-eight, the next begins, ‘I understand that to have a poem dedicated to you / is a horrifying burden’. But this is in many ways a book of dedications, as reconstituted emails to fellow poets Richard and Cilla, or recollections of recklessness with friends Niki, Kim and Andy, or negging his painter friend Jon with insults compiled and passed off as poetry such as ‘lots of cocks in that one’ and ‘barbecue needs a clean’.

Nick may outwardly disavow unearned puff and pomp around poetry, to the extent that his own poems will warmly shake your hand and insist ‘I can tell that you’re all better cunts than I, comrades’ for having made it through the first stanza. Now, having been spooked by the whole luminosity business, against the conventions of the launch speech’s sweet nothings, I have thus aimed to offer a grounded account of Nick’s book which has nonetheless convinced me of his shimmering and possibly bioluminescent brilliance.

You can’t get around the sugarwork – the act of writing a book of poems

is inherently a wincingly sincere confection, and any collection is an

elaborate tower of custardy puff-pastries held together with molten sugar and a

prayer. Yet here comes Nick, dismantling the croquembouche and lobbing

profiteroles into the crowd! We would be fools not to welcome them. Let us go

forth proudly and be stupefied.

The Stupefying (paperback, $25) is out now.